Work-leave rotation among general practitioners in Norwegian municipalities

Main findings

The use of work-leave rotation schemes for general practitioners increased in Norway in the period 2015–23.

The most common form of rotation was two weeks of work, followed by four weeks of leave.

Work-leave rotation was most frequently used in Norway's least central municipalities.

The analysis revealed that this work schedule has most likely not been evaluated, nor is there a national framework for working hours and specialist training.

Recruiting and retaining GPs represents a major challenge for many municipalities (1). The challenges are most prominent in the least central municipalities (2–4). Some municipalities have introduced work-leave rotation (aka 'North Sea shift'), whereby the doctors work continuously for shorter periods followed by longer periods of leisure time. We have chosen to use the term 'work-leave rotation' about this form of work, a choice inspired by the collective agreement for the manufacturing industry (5), where a rotation schedule consisting of 14 days of work and 28 days off is regulated by the system of agreements.

In a Norwegian context, work-leave rotation is also referred to as 'accumulation schedules' (6). Moland and Bråthen (7) describe these as popular among employees. In the petroleum industry, the long distances between home and workplace are a key reason. In the healthcare sector, where such schedules seem to be most prevalent in the nursing and care sector, the arguments for such arrangements include concerns for service users, expectations for less sickness absence, less involuntary part-time work and easier recruitment.

Internationally, organisation forms such as fly-in, fly-out or drive-in, drive-out are reminiscent of the work-leave rotation schemes for GPs (8). A personal statement published in 2012 advocated such schedules as a solution to the shortage of doctors in rural parts of Australia (9).

Little research has been undertaken in the health services regarding the prevalence, causes and consequences of introducing work-leave rotation, nationally or internationally. The objective of this study is to identify and describe the municipalities that have chosen to establish work-leave rotation for GPs. We wished to investigate characteristics of the various rotation schemes and the doctors who are working in them. In addition, we wished to investigate the reasons why the municipalities came to choose work-leave rotation and the experiences gained.

Material and method

Design

We conducted an exploratory multiple-case study using quantitative as well as qualitative data from different municipalities that have introduced work-leave rotation for GPs. The case-study methodology is flexible and permits a practice-oriented and holistic approach that includes multiple perspectives, with a variety of data sources that help provide insight (10, 11). We examined work-leave rotation schemes for GPs as a phenomenon, and the cases consisted of municipalities that had organised (parts of) their GP services in this way. In the study, we used descriptive statistics from Statistics Norway, the GP register and some simple questions for doctors who were employed in such positions, as well as qualitative in-depth interviews with municipal healthcare leaders to obtain insight into the organisation, background, assessments of and experiences gained from the schemes. The interview guide included both open-ended and pre-coded questions about the schemes (see the Appendix).

The research team consisted of two specialist trainees in general practice (EEP and MBH), a specialist in general practice with long-standing experience as a contract GP (AF) and a professor of health services research with broad research experience in the area of general practice services (BA). EEP and MBH have both previously been employed in a work-leave rotation scheme.

Participants

No comprehensive overview of the municipalities that practise work-leave rotation was available. We therefore attempted to identify the relevant municipalities by contacting all county governors and reaching out through the 'Allmennlegeinitiativet' ('the GP initiative') on Facebook, as well as using our personal networks. The objective was to identify municipalities that had introduced some form of work-leave rotation before 1 June 2023. Rotating schedules for doctors in the specialist health services or private clinics were not included. We wished to contact municipal healthcare leaders (municipal chief medical officers, directors of health and care services, heads of medical centres or A&E centres) in the municipalities concerned. To obtain supplementary demographic information on the doctors who were employed in a work-leave rotation scheme, the healthcare leaders provided us with the names of the local doctors, who were subsequently contacted by telephone.

Quantitative data

We obtained data from Statistics Norway on population size and centrality class for the relevant municipalities and for Norway as a whole. From the contract GP register we obtained data sets on locum contracts that contained the contract ID, start and end date, full-time percentage and the municipality number. Details on age, specialty and previous workplace for the doctors following a work-leave rotation scheme were obtained from the doctors themselves (see above). The in-depth interviews with healthcare leaders provided supplementary qualitative information on matters such as salary level, the nature of the rotation scheme (weeks on/off) and the number of applicants for positions.

Qualitative data

After obtaining written consent, the in-depth interviews with municipal healthcare leaders (chief municipal medical officers or directors of health and care services) were conducted by video chat or telephone (EEP and MBH). Based on an interview guide (see Appendix), the participants were invited to give a description of the work-leave rotation schedule used in their municipality, the background to its establishment, and their experiences and assessments. In the very few cases where we were unable to contact the healthcare leader, we conducted a corresponding interview with a doctor who was in the rotation scheme and employed by the municipality in question. We conducted qualitative interviews with a total of 16 healthcare leaders and 14 doctors working in a rotation scheme (13 women). Of these, 14 were video interviews and six were telephone interviews, all lasting from 45 to 90 minutes each.

EP and MBH transcribed the audio recordings of the video interviews. The telephone and video interviews were documented through notes taken along the way (by EP and MBH). The transcripts and notes formed the basis for the thematic analysis.

Analysis

We produced simple descriptive statistics of the collected data material to characterise the municipalities, doctors and variants of work-leave rotation. We analysed the use of locums based on all signed locum contracts for the two years preceding the introduction of work-leave rotation and until 31 December 2022. Characteristics of the municipalities (population size and centrality class) and the appurtenant doctors (age, sex, specialty) were combined with figures for Norway as a whole. For the analyses, we used the SPSS (IBM Corp.) tool.

We assessed the attractiveness of work-leave rotation for doctors by examining the number of applicants to the most recent vacancy announcements. Changes in the number of locums associated with the lists in question after the introduction of work-leave rotation were used as a measure of stabilisation of the GP service.

The analysis of the transcripts and notes from the interviews was performed as a thematic analysis (12). All the authors read the material thoroughly and identified codes and text strings that could help describe the experiences with work-leave rotation. During the analysis process, BA, AF and MBH met regularly to discuss and evaluate findings. Early in the process, preliminary topics were defined, including 'Various justifications for having a North Sea shift schedule', 'Results, consequences and evaluation of the North Sea shift schedule' and 'On an unclear legal basis and within a temporary organisational framework'. We subsequently sorted the codes and meaning units into these preliminary topics, condensed the text, reformulated the names of the topics to suitable result headlines and wrote the results chapter.

Ethics

The collection and storage of data were assessed and approved by the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (now named Sikt), with the reference number 914345. All interviewees in the qualitative interviews provided written consent. The doctors who participated in the brief telephone interviews undertaken to collect demographic information provided oral consent.

Results

The municipalities

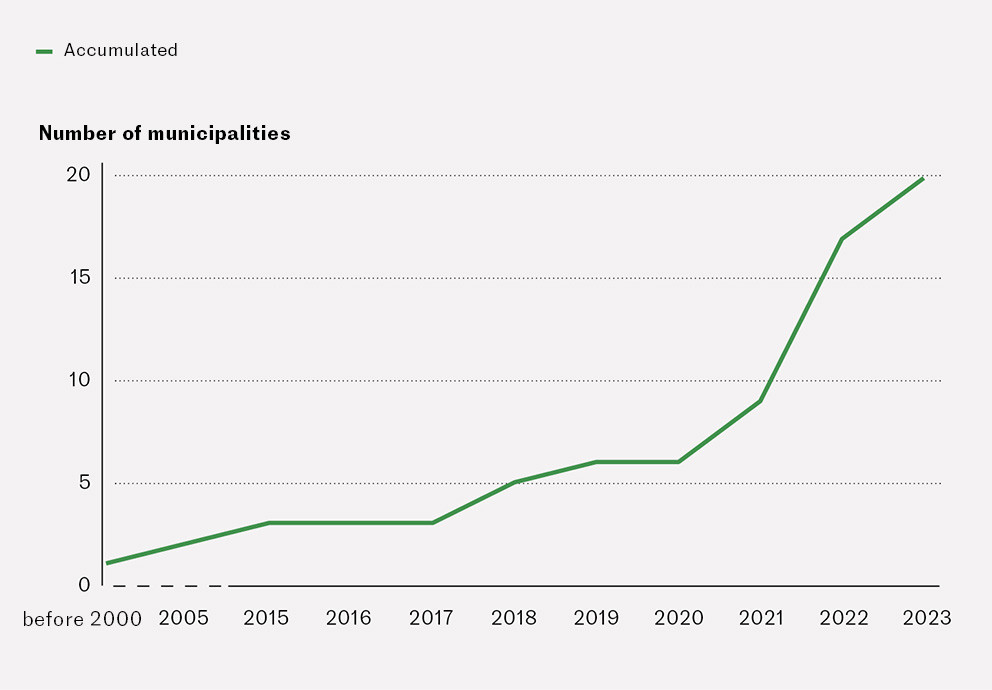

We identified 25 municipalities that had some kind of work-leave rotation scheme for doctors as of 1 June 2023. Five of these municipalities did not respond to our inquiry or declined to participate in the study. Therefore, 20 municipalities (20/25, 80 %) were included. Figure 1 shows that 14 of 20 municipalities (70 %) had established work-leave rotation after 2020. These municipalities had a smaller population than the national average (average: 5 396 vs. 15 419, median: 2 759 vs. 5 163), and 13 of the 20 municipalities were located in Northern Norway, i.e. Nordland (n = 6) or Troms og Finnmark counties (n = 7). The remaining municipalities were located in Vestfold og Telemark (n = 2), Innlandet (n = 2), Vestland (n = 2) and Møre og Romsdal counties (n = 1). On the centrality scale, where 1 is most central and 6 least central, the municipalities were in centrality classes 4 (3 municipalities), 5 (3 municipalities) and 6 (14 municipalities).

The work-leave rotation schemes

There was some variation in the distribution of working and leave weeks, but in 13 of 20 municipalities the doctors worked for two weeks and had four weeks off. Other variations included two weeks on and three weeks off (n = 3), one week on and two weeks off (n = 1), one week on and three weeks off (n = 1), one week on and four weeks off (n = 1), and three weeks on and three weeks off (n = 1). All these arrangements also included out-of-hours duty. In six of the municipalities, the arrangement consisted entirely of this, sometimes also including additional tasks for the municipality, for example serving as medical officer in a nursing home. In 12 of 14 municipalities where the doctors also worked in the daytime, the doctors received a fixed salary for the daytime hours, whereas the form of remuneration varied more for out-of-hours work; a higher proportion of these doctors earned income from self-employment when compared to those who worked in the daytime. In 12 of 14 municipalities where the doctors were responsible for a patient list, the doctor had a personal practice licence. In the other two, one doctor held the practice licence, while the other doctors who practised work-leave rotation covered this list while on duty in the municipality.

The doctors

Based on the interviews with the healthcare leaders, we identified a total of 64 doctors working in a rotation scheme in the municipalities concerned. These doctors provided qualitative descriptive data about themselves by telephone. Compared to national figures, they were somewhat younger than GPs in general (average: 43 years versus 50 years). The doctors' age was normally distributed (visually assessed). Compared to Norway as a whole, there was a greater proportion of men (59.4 % versus 54.5 %) and a smaller proportion of specialists in general practice (45.3 % versus 64.4 %). The doctors who were not specialists in general practice were trainee specialists in general practice, or the municipalities were taking active steps for them to become trainee specialists in general practice. Altogether 63 % of the trainee specialists participated in supervision groups. There were on average ten applicants (median 6, range 1–28) for each vacancy announcement encompassed by the work-leave rotation scheme. Somewhat less than half of the doctors had worked as GPs prior to their current job with work-leave rotation, the others came from jobs in hospitals, other jobs in primary health care or other kinds of rotation schedules, or they had just completed specialisation training or worked in other types of jobs.

Stabilisation

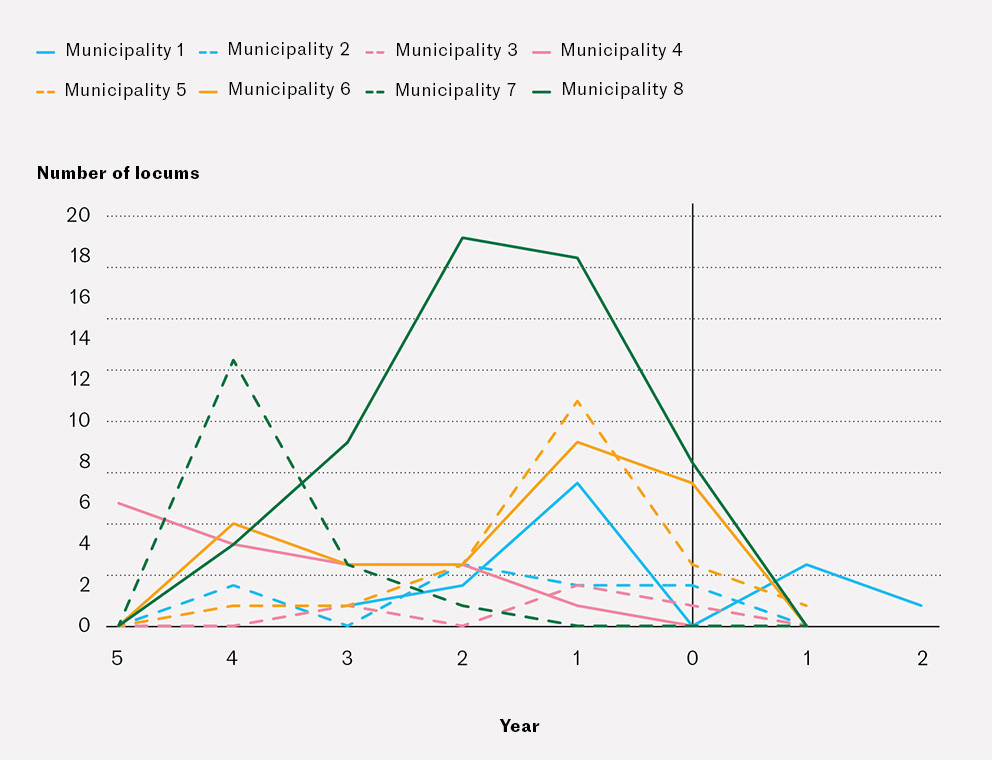

Figure 2 shows locum contracts in the GP service before and after the introduction of work-leave rotation in the selected municipalities. The sample consists of eight municipalities where the entire medical service is organised on the basis of work-leave rotations. Some municipalities had reduced their use of locums, while in others there was no change.

The path to the work-leave rotation scheme

Healthcare leaders described how the municipalities for various reasons had come to choose work-leave rotation. The fact that the doctors were forced to work frequent duty periods was one key reason. To retain these duty-weary doctors in the GP service and make the municipality more attractive to new doctors, work-leave rotation was introduced. Many healthcare leaders reported to have received no responses to regular vacancies for GPs, but if a vacancy was announced with work-leave rotation, a number of well-qualified applicants responded. One informant reported that there had been zero applicants for three permanent GP positions, but three doctors had later come forward with a request for work-leave rotation. One informant described the work-leave rotation scheme as 'a solution that pushed itself to the fore', while another referred to it as the solution to 'a crisis situation'.

Several informants reported that over time, the municipality had used successive locums to staff the out-of-hours service. Many had chosen to use doctors on work-leave rotation in the out-of-hours service because they wanted more stable doctors who were attached to and knowledgeable about the municipality. They were dissatisfied with the staffing agencies or felt that a disproportionate amount of resources were spent on administering the use of locums. Some informants were unable to give a reason why their municipality had chosen work-leave rotation; they had not been involved in the decision because they were employed later and had not found any written documentation of the process.

Inadequate legal and contractual framework

The establishment of work-leave rotation typically started with a working group consisting of the municipal chief medical officer, the chief municipal executive and the director of health and care services. Frequently, the municipalities had received advice from others that were ahead of them in the establishment of work-leave rotation. Common to all the municipalities was their broad administrative authority to design the arrangement. Many of the informants pointed out that the work-leave rotation scheme was not well embedded in a national legal framework. Some municipalities had contacted the Norwegian Medical Association or the Norwegian Association of Local and Regional Authorities (KS) for advice on the design of contracts. Some of the municipalities had been advised to undertake a study on the doctors' workloads, and that the work-leave rotation scheme needed to be organised as a local trial arrangement with evaluations undertaken underway and a final evaluation after two years. There were differences and unclarities in the contracts, especially related to working hours and holidays. One healthcare leader stated:

'I believe that very few Norwegian municipalities really know what they are doing. Probably very few of the contracts are legal.'

Work-leave rotation and specialisation training

Some municipalities that hired a specialty registrar used the mandatory and non-mandatory time available to ensure compliance with the specialisation requirement for at least 50 % curative work on an unselected population. The mandatory working hours encompassed the time that the doctor was physically present at work in the municipality, while the non-mandatory working hours included the period when the doctor was 'off duty', but available digitally to a limited extent. It varied whether the trainee specialists in general practice in the work-leave rotation scheme were offered participation in group supervision. Training course attendance and group supervision needed to take place during the off periods. We heard several reports about healthcare leaders and municipal chief medical officers who signed applications for approval of specialty training in general practice, so that the doctor in the work-leave rotation scheme had their specialisation training approved, despite a previous recommendation from the specialisation committee not to approve the training. One healthcare leader told us:

'I have contacted the Directorate of Health and person X with a view to suggesting a solution. I have understood that the Directorate of Health takes a positive view of establishing a pathway to specialisation for doctors working the so-called North Sea shift.'

Stabilisation, vulnerability and flexibility

A recurrent feedback message from the informants was that the hiring of locum doctors was reduced after the introduction of work-leave rotation. The informants were told by the permanent doctors that the rotation schedule gave the doctors more time for the patients on their own list as well as respite, especially when the doctors who were on a rotational schedule were assigned to out-of-hours or on-call duty. Many GPs who had considered resigning chose to remain, and weary GPs who previously had applied for a reduced FTE could now work full-time. Two municipalities had reestablished the local out-of-hours service.

Many healthcare leaders described doctors' absence due to sickness or for other reasons as a vulnerability inherent in this arrangement. To counteract this vulnerability, many municipalities had made arrangements for mutual coverage during periods of absence between the doctors in the work-leave rotation scheme and/or the permanent GPs. Some had made agreements with neighbouring municipalities, while others were discussing whether to draw up a mandatory assignment list.

In the interviews, the word flexibility kept recurring. Work-leave rotation gave the doctors flexibility with regard to their off-duty periods, and the doctors demonstrated flexibility by turning up at short notice in cases of illness and exchanging shifts and work periods with their colleagues as needed.

When it came to following up the responsibility for patient lists, most informants believed that having permanent doctors was better than having doctors on work-leave rotation, which in turn was far better than locums. In cases where doctors on work-leave rotation were responsible for a patient list, procedures were established for transfer of information and follow-up appointments. In one municipality, the local office of the Norwegian Labour and Welfare Administration (NAV) had reported that certified sickness absence periods lasted longer, most likely to permit the patients to meet with the same doctor at their follow-up appointment.

The informants broadly agreed that work-leave rotation was not an optimal solution for the GP service. Where there had previously been one or two doctors, there were now three. The scheme might thus drain the municipality of GPs if working as a doctor in a work-leave rotation scheme appears more attractive. The scheme was described as a compromise that functioned better and was cheaper than having incidental locums. One doctor in work-leave rotation said:

'I've been thinking that in a national perspective, the arrangement is not sustainable – the municipalities are drained of good GPs.'

Discussion

We found that a growing number of municipalities, particularly the least central ones, are establishing work-leave rotation schemes for GPs. The most common rotation schedule was two weeks of work followed by two weeks of leave. All the positions with work-leave rotation in our study included out-of-hours work, and some of them consisted entirely of this. In a survey of 205 participating municipalities conducted by KS in September 2023, 18 % reported to have 'an arrangement for North Sea/long shift for doctors who perform out-of-hours duty' (A. Jensen, KS, personal communication). Among municipalities with less than 2 000 inhabitants, this proportion was 38 %, while the proportion was lowest (4 %) in municipalities with 15 000–50 000 inhabitants. In municipalities with 50 000 inhabitants or more, the proportion was 14 %. These figures indicate that this type of arrangement is more common than has been captured in our study.

The emergence of work-leave rotation

The recruitment challenges in the GP service are likely associated with the increased workload on doctors in the contract GP scheme (13). Work-leave rotation appears to have been partly spurred on by municipalities searching for a solution to their recruitment problems and partly by doctors searching for attractive employment conditions. We have no evidence to conclude whether doctors' interest in work-leave rotation is an expression of changes in their employment preferences, or whether the increase in work-leave rotation in the GP service might be the start of a reorganisation of the GP service in rural municipalities.

A survey among medical students in England showed that many did not envisage working full time because of the large expected workload, but wanted to emigrate to work as a doctor in another country or would opt not to work as a doctor (14). The findings are indicative of changed preferences among young doctors, although England and Norway might not be directly comparable. A similar study among Danish foundation doctors showed that those who considered working as GPs were more interested in part-time work than those who would not consider working in general practice (15).

Legal aspects

Work-leave rotation for GPs is not regulated in any collective agreements, contractual framework or regulations (16–18). Work-leave rotation challenges many of the inherent objectives of the contract GP scheme and violates existing regulations pertaining to contract GP activity in terms of the requirement for one contract GP per patient list and continuous curative activity throughout the year (28 hours per week, 44 weeks per year). Even though work-leave rotation is unregulated, this does not mean that it is illegal. Contracts involving work-leave rotation can be subject to local bargaining and must comply with the provisions in the Working Environment Act and the Holidays Act. For municipalities with an existing or planned work-leave rotation scheme, it would most likely save resources if regulated and collective agreements laying down basic principles and guidelines were put in place.

Specialisation in work-leave rotation schemes

The current regulations for specialisation training presume that primarily only specialists in general practice can be employed in work-leave rotation schemes, but our findings indicate that this rule is not observed. The specialty committee (19) and the Directorate of Health (20) consider that work-leave rotation in general practice is not compatible with the requirement in the old specialty training scheme in general practice for at least a 50 % position in open, unselected practice and continuous service for at least three months. The requirements in the new specialisation scheme are less categorical, but our study indicates that expectations are unclear to the municipalities and the doctors regarding how service in a work-leave rotation scheme will count as part of their specialisation training and qualify them for participation in group supervision, for example. More detailed guidelines concerning types of acceptable rotation schemes are called for, as well as methods for calculating the percentage of open, unselected practice in a GP contract.

Could better previsions be made for specialisation in general practice in the work-leave rotation schemes, so that good quality of the training and the medical services can be ensured, especially in rural districts? There is good empirical evidence of the necessity to train healthcare personnel locally in order to retain doctors and to ensure good contextual understanding and quality (21–23). Most of the municipalities that had a specialty registrar on work-leave rotation required attendance on training courses and group supervision during the leave periods. Moreover, some municipalities required the doctors to work online from home to a limited extent, so-called non-mandatory time. The long leave periods could be an opportunity to establish a more structured training programme in collaboration with a professional community in a more central location (where the doctors frequently live when on leave), for example by linking doctors, medical centres and municipalities in rural areas with their counterparts in more central locations. We know that in Iceland, large medical centres in Reykjavik have signed agreements with doctor's surgeries in rural areas on coverage of medical services in a permanent rotational scheme (S. Arnardottir, personal communication). This could be a kind of remote variant of the Norwegian scheme known as 'Senjalegen' (24). Such schemes could probably ensure the supervision and follow-up of general practice trainees.

It is important to understand and address the opportunities and risks inherent in using work-leave rotation as a way of working in the GP service. Our study indicates that this form of work makes for good recruitment, establishes availability and some form of continuity, albeit somewhat piecemeal, for the patients.

Strengths and weaknesses

In this multiple-case study, we used pragmatism (25) as a theoretical basis to analyse and integrate different data sources to elucidate the research question. In our case, we believe this method provides a broader and more holistic picture of the phenomenon investigated (10, 11) and thereby represents a strength of our study.

A further strength is that 20 of 25 municipalities identified as having a work-leave rotation scheme in their GP service participated. This resulted in a large volume of data on various work-leave rotation schemes. An unpublished survey undertaken by KS (see above) may indicate, however, that we have not captured all municipalities that have such schemes.

We chose to limit the study to the experiences and assessments of healthcare leaders, as well as descriptive statistics on the municipalities, the work-leave rotation schemes and the doctors working in them. We have not investigated the experiences gained by the doctors and patients from such schemes, quality-related aspects and economic issues. Work-leave rotation schemes appear to be popular among municipalities and doctors alike. Tucker (26) emphasises the need for caution when interpreting self-reported experiences with a scheme that is as popular as work-leave rotation, due to a higher risk of biased descriptions and underreporting of negative experiences.

It is a weakness that we have not been able to study experiences with work-leave rotation schemes over time. The small number of municipalities and a short observation period mean that we have no basis to conclude whether work-leave rotation impacts on the use of locums.

Two of the researchers in the team were previously employed in work-leave rotation schemes, where they met with challenges related to their specialisation training. During the planning, data collection and analysis stages we have critically discussed how these experiences may have impacted on the research process. This has helped fine-tune the questions related to both merits and disadvantages of work-leave rotation schemes.

Conclusion

This study shows that the prevalence of work-leave rotation schemes is increasing in the GP service. The least central municipalities have the greatest proportion of work-leave rotation schemes. We found a number of variants of this scheme, all of which involved GP recruitment. There are no data on the long-term effects of work-leave rotation schemes. Our findings show that work-leave rotation likely departs from the traditional organisation of GP services in a way that challenges current regulations for employees, specialisation training in general practice and the intention behind the contract GP scheme. We urge the national health authorities and the Norwegian Medical Association to address these challenges. Future studies should investigate whether work-leave rotation helps retain doctors, and whether this can be combined with specialisation training in general practice. The more long-term consequences of such schemes for the population, doctors and other healthcare personnel should also be investigated-

The article has been peer reviewed.

- 1.

Ekspertutvalget for gjennomgang av allmennlegetjenesten. Gjennomgang av allmennlegetjenesten. Ekspertutvalgets rapport. https://www.regjeringen.no/contentassets/092e9ca0af5e49f39b55c6aded2cf18d/230418_ekspertutvalgets_rapport_allmennlegetjenesten.pdf Accessed 8.10.2024.

- 2.

Abelsen B, Gaski M, Brandstorp H. Fastlegeordningen i kommuner med under 20 000 innbyggere. NSDM-rapport 2018. https://nsdm.no/arkiv/filarkiv/File/rapporter/Rapport_Fastlegeordningen_NSDM_2016.pdf Accessed 8.10.2024.

- 3.

Gaski M, Abelsen B. Fastlegetjenesten i Nord-Norge. NSDM-rapport 2016. https://www.nsdm.no/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Endelig-versjon-3-mai-2018-Rapport-om-fastlegetjenesten-i-Nord-Norge.pdf Accessed 8.10.2024.

- 4.

Abelsen B, Gaski M, Brandstorp H. Varighet av fastlegeavtaler. Tidsskr Nor Legeforen 2015; 135: 2045–9. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 5.

Lovdata. Industrioverenskomsten LO – Verksted 2022–2024. https://lovdata.no/dokument/TARO/tariff/taro-83/KAPITTEL_vo-9.#KAPITTEL_vo-9 Accessed 31.1.2024.

- 6.

Nicolaisen H. Innarbeidingsordninger og familieliv – erfaringer fra helsesektoren og industrien. Søkelys på arbeidslivet 2012; 29: 224–41. [CrossRef]

- 7.

Moland LE, Bråthen K. Forsøk med langturnusordning i Bergen kommune. Fafo-notat 2011:07. https://www.fafo.no/en/publications/fafo-notes/forsok-med-langturnusordninger-i-bergen-kommune Accessed 8.10.2024.

- 8.

Hussain R, Maple M, Hunter SV et al. The Fly-in Fly-out and Drive-in Drive-out model of health care service provision for rural and remote Australia: benefits and disadvantages. Rural Remote Health 2015; 15: 3068. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 9.

Margolis SA. Is Fly in/Fly out (FIFO) a viable interim solution to address remote medical workforce shortages? Rural Remote Health 2012; 12: 2261. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 10.

Carolan CM, Forbat L, Smith A. Developing the DESCARTE Model: The Design of Case Study Research in Health Care. Qual Health Res 2016; 26: 626–39. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 11.

Sibbald SL, Paciocco S, Fournie M et al. Continuing to enhance the quality of case study methodology in health services research. Healthc Manage Forum 2021; 34: 291–6. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 12.

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006; 3: 77–101. [CrossRef]

- 13.

Skyrud KD, Rotevatn TA. Utvikling i fastlegenes arbeidsmengde og situasjon over tid. https://www.fhi.no/contentassets/6a3405e0bbc54fc4abcb72ededf60434/utvikling-i-fastlegenes-arbeidsmengde-og-situasjon-over-tid-kunnskapsgrunnlag-rapport-2023.pdf Accessed 8.10.2024.

- 14.

AIMS Collaborative. Career intentions of medical students in the UK: a national, cross-sectional study (AIMS study). BMJ Open 2023; 13. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2023-075598. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 15.

Gjessing S, Guldberg TL, Risør T et al. Would you like to be a general practitioner? Baseline findings of a longitudinal survey among Danish medical trainees. BMC Med Educ 2024; 24: 111. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 16.

SFS 2305 ("Særavtalen"). 01.01.2022- 31.12.2023. Avtalen er prolongert til 30.01.2024. https://www.legeforeningen.no/jus-og-arbeidsliv/avtaler-for/leger-ansatt-i-kommunen/KS-leger-ansatt-i-kommunen/sentrale-avtaler/sfs-2305-Saeravtalen/ Accessed 31.1.2024.

- 17.

KS. ASA 4310 for perioden 2024-2025. Rammeavtale mellom KS og Den norske legeforening om allmennlegepraksis i fastlegeordningen i kommunene. https://www.ks.no/contentassets/dbb79dcf070148d6a2aab23d344c03e0/ASA-4310-2024-25.pdf Accessed 31.1.2024.

- 18.

Helse- og omsorgsdepartementet. FOR-2012-08-29-842 Forskrift om fastlegeordning i kommunene. https://lovdata.no/dokument/SF/forskrift/2012-08-29-842 Accessed 31.1.2024.

- 19.

Den norske legeforening. Deltakere i veiledningsgrupper for allmennmedisin. https://www.legeforeningen.no/fag/spesialiteter/Allmennmedisin/Veiledningsgrupper/deltakere-i-veiledninngsgrupper-for-allmennmedisin/#Blir%20Nordsj%C3%B8turnus%20ansett%20som%20spesialistutdanning%20og%20som%20del%20%C3%A5pen%20uselektert%20praksis Accessed 2.2.2024.

- 20.

Helsedirektoratet. Ansettelseskrav, utdanningstid, fravær og overgangsregler. https://www.helsedirektoratet.no/tema/autorisasjon-og-spesialistutdanning/spesialistutdanning-for-leger/artikler/ansettelseskrav-utdanningstid-fravaer-ogovergangsregler Accessed 2.2.2024.

- 21.

Strasser R. Learning in context: education for remote rural health care. Rural Remote Health 2016; 16: 4033. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 22.

Verma P, Ford JA, Stuart A et al. A systematic review of strategies to recruit and retain primary care doctors. BMC Health Serv Res 2016; 16: 126. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 23.

Morris CG, Johnson B, Kim S et al. Training family physicians in community health centers: a health workforce solution. Fam Med 2008; 40: 271–6. [PubMed]

- 24.

Senja kommune. Senjalegen / Fastlege. https://www.senja.kommune.no/tjenester/helse-og-omsorg/helsetjenester/legehjelp/fastlege/ Accessed 6.2.2024.

- 25.

Morgan DL. Pragmatism as a Paradigm for Social Research. Qual Inq 2014; 20: 1045–53. [CrossRef]

- 26.

Tucker P. Conditions of Work and Employment Programme. Compressed working weeks. Conditions of Work and Employment Series No. 12. https://www.ilo.org/sites/default/files/wcmsp5/groups/public/@ed_protect/@protrav/@travail/documents/publication/wcms_travail_pub_12.pdf Accessed 8.10.2024.

En rotasjonsordning for allmennleger bryter med de funksjoner og egenskaper som ligger i fast lege over tid, tidligere beskrevet med uttrykket KOPF (Kontinuerlig, Omfattende, Personlig, Forpliktende). Det er i realiteten en vikarstafett med kjente vikarer over litt tid.

Det er lov å anta at slike rotasjonsordninger gir i motsetning til fastlegeordningen og fast lege, flere innleggelser i sykehus, flere henvisninger, høyere dødelighet, høyere sykefravær og flere uføretrygdede.

Artikkelen omhandler rotasjonsordning i allmennpraksis (1), men liknende forhold kan også gjelde sykehusleger. Jeg har egne dårlige erfaringer med "nordsjøturnus" fra mitt arbeid på sykehus. Jeg opplevde at modellen ble innført ved kirurgisk avdeling der jeg arbeidet. Motvillig måtte jeg tiltre ordningen. Alternativet ville vært å selge hus, flytte med familien til et annet sted, skaffe ny jobb til meg selv og min ektefelle. Min hovedinnvending var at ingen blir en bedre kirurg av å være borte fra faget store deler av året. Jeg opplevde at legene ble perifere i sykehusmiljøet og ansvar pulverisert.

Ved slutten av karrieren kan man i en rotasjonsordning "flyte" på opparbeidet erfaring noen år frem til pensjonsalder. For yngre kolleger, derimot, vil rotasjonsordning sterkt redusere mulighetene til å skaffe seg erfaring, på grunn av de lange friperioder. "Øvelse gjør mester", sies det. Da er det lite lurt å redusere mulighetene for øvelse/vedlikehold av ferdigheter, slik en rotasjonsordning medfører. For samfunnet mener jeg dette er dårlig utnyttelse av legene. Faglig mener jeg det er dårlig også for legene, selv om det økonomisk kan være greit å få full årslønn for 4-5 måneders arbeid.

Litteratur

1. Prestgaard EE, Fosse A, Abelsen B et al. Rotasjonsordning for allmennleger i norske kommuner. Tidsskr Nor Legeforen 2024; 144. doi: 10.4045/tidsskr.24.0089