Aortitis triggered by granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) is a rare, but relevant differential diagnosis in patients with fever and elevated inflammatory markers receiving G-CSF-supported chemotherapy.

A man in his late sixties, who had undergone laparoscopic prostate surgery ten years earlier and had hypertension and atrial fibrillation, was diagnosed with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma localised in the base of his tongue. Lymphoma treatment was initiated with chemotherapy, consisting of rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisolone (R-CHOP), as well as granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) with pegfilgrastim 6 mg subcutaneously on the third day of each chemotherapy cycle.

Twelve days after the first cycle, the man was admitted to hospital with fever, body aches and a diminished general condition that had lasted for two days. In the emergency department, his ear temperature was 38.5°C, blood pressure 132/75 mm Hg, pulse rate 85/min, respiratory rate 23/min and oxygen saturation 96 % in room air. C-reactive protein (CRP) was 104 mg/L (reference value: < 5), and neutrophil granulocytes were 12.6 × 109/L (1.80–6.90). Evaluation showed no signs of focal infection, and intravenous antibiotics consisting of phenoxymethylpenicillin 1.2 g × 4 and gentamicin 4 mg/kg × 1 were promptly initiated due to suspicion of infection with unknown focus.

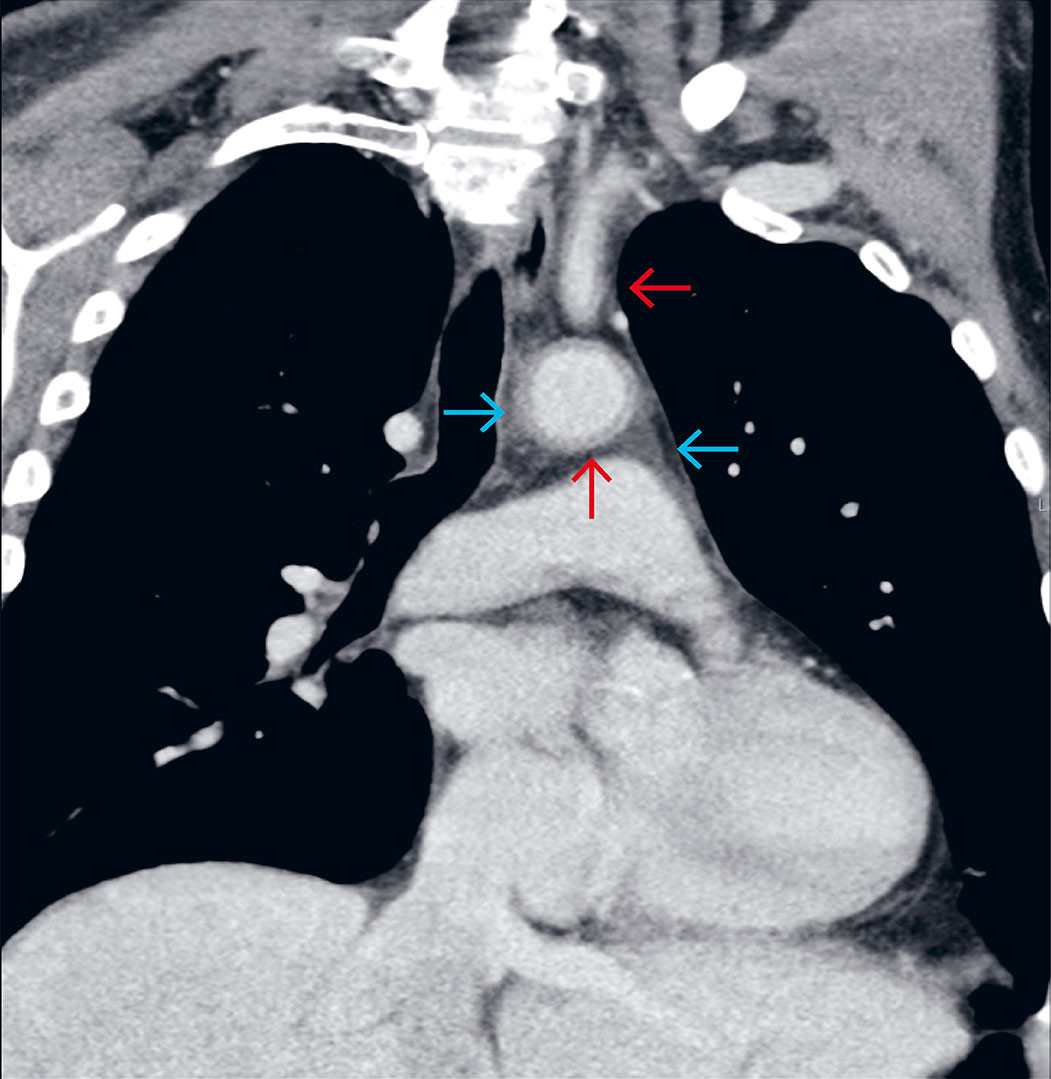

Due to a lack of response to treatment after three days, the antibiotics were changed to intravenous cefotaxime 2 g x 3, combined with metronidazole 1.5 g x 1. On day four, the treatment was again switched to intravenous meropenem 1 g x 3 and vancomycin 1 g x 2. CRP had risen to 331, and the patient was still experiencing fever spikes > 38.7 °C. He was also now reporting mild chest pain but was considered to have unusually few signs of infection. All cultures were negative, a chest X-ray was normal, and transthoracic echocardiography showed no signs of endocarditis. On day four, a contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest, abdomen and pelvis was performed, leading to the correct diagnosis. The CT scan revealed vasculitic changes in the aorta and several branch vessels (Figure 1). G-CSF-induced aortitis was considered the likely diagnosis, and after an interdisciplinary discussion, peroral treatment with prednisolone 40 mg x 1 was initiated. Over the next few days, the patient became afebrile, and CRP decreased significantly. Antibiotics were discontinued after seven days, and the patient was discharged in good health after ten days. Prednisolone was tapered and discontinued over the course of three months. The lymphoma was successfully treated with four R-CHOP cycles, followed by two cycles of rituximab monotherapy. G-CSF was not administered again after the first cycle. Two years after initiating treatment, there were still no signs of lymphoma or vasculitis relapse.

Discussion

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma is a high-grade lymphoma that often responds well to chemotherapy. A common problem during treatment is neutropenic fever (1). G-CSF is given to reduce the risk of severe infections and thereby maintain high dose intensity, which is crucial for treatment outcome. G-CSF typically has few side effects. Large vessel vasculitis is a rare side effect, with an estimated incidence ranging from ≥ 1/10,000 to < 1/1000 (2–6). Published case reports suggest that the condition is most common in women (3), although this can partly be explained by the high proportion of breast cancer and gynaecological cancers in the literature. Pegylated forms of G-CSF may have a stronger association with aortitis than non-pegylated formulations (7–8).

Vasculitis should be considered as a differential diagnosis in patients with fever and elevated inflammatory markers following G-CSF treatment, particularly if antibiotic therapy is ineffective. The median onset of symptoms is eight days after G-CSF treatment (3). Pain in the neck and chest regions can occur but is a nonspecific symptom. The exact pathogenesis is unknown, but it is established that G-CSF induces large-scale mobilisation of neutrophils (1, 9). One possible mechanism is therefore that the high number of circulating neutrophils and inflammatory cytokines from stimulated myeloid cells induce vasculitis. A high tumour burden has been suggested as a risk factor (3), but this was not observed in this case report.

Imaging is crucial for diagnostics and preventing unnecessary antibiotic treatment. Ultimately, the CT scan with contrast in the portovenous phase led us to the correct diagnosis. For targeted investigations or follow-up of extracranial vasculitis, positron emission tomography with integrated CT (PET/CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are more suitable modalities (10). Malignancy and large vessel vasculitis sometimes occur simultaneously, but this is more often a coincidence than a paraneoplastic phenomenon. True paraneoplastic vasculitis typically affects small and medium-sized vessels and is more common in hematologic cancers than in other types of cancer (11). Paraneoplasia cannot be ruled out in our patient, but we believe that G-CSF was most likely the trigger. Other diagnostic tests showed no evidence of an underlying rheumatic condition. Prednisolone was tapered relatively quickly compared to, for example, treatment for temporal arteritis. The role of corticosteroids in treating this condition remains unclear, and further research is needed to determine the most effective approach. In a systematic review article from 2021, with 49 reported cases of G-CSF-induced aortitis, no significant difference was found in the time from onset to remission with or without corticosteroid treatment (3). Discontinuation of G-CSF is important for achieving remission from vasculitis.

The patient has consented to publication of the article.

The article has been peer-reviewed.

- 1.

Mhaskar R, Clark OA, Lyman G et al. Colony-stimulating factors for chemotherapy-induced febrile neutropenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014; 2014: CD003039. [PubMed]

- 2.

Asif R, Edwards G, Borley A et al. Granulocyte colony stimulating factor (G-CSF)-induced aortitis in a patient undergoing adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. BMJ Case Rep 2022; 15. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2021-247237. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 3.

Hoshina H, Takei H. Granulocyte-colony stimulating factor-associated aortitis in cancer: A systematic literature review. Cancer Treat Res Commun 2021; 29. doi: 10.1016/j.ctarc.2021.100454. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 4.

Taimen K, Heino S, Kohonen I et al. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor- and chemotherapy-induced large-vessel vasculitis: six patient cases and a systematic literature review. Rheumatol Adv Pract 2020; 4. doi: 10.1093/rap/rkaa004. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 5.

Nishimura M, Morita M, Okuyama Y et al. A Case of Aortitis Caused by Pegfilgrastim Use during Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy for Treating Breast Cancer. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho 2022; 49: 573–6. [PubMed]

- 6.

Felleskatalogen. Ziextenzo. https://www.felleskatalogen.no/medisin/ziextenzo-sandoz-659913?markering=0 Accessed 4.12.2024.

- 7.

Lee SY, Kim EK, Kim JY et al. The incidence and clinical features of PEGylated filgrastim-induced acute aortitis in patients with breast cancer. Sci Rep 2020; 10: 18647. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 8.

Yukawa K, Mokuda S, Yoshida Y et al. Large-vessel vasculitis associated with PEGylated granulocyte-colony stimulating factor. Neth J Med 2019; 77: 224–6. [PubMed]

- 9.

Theyab A, Algahtani M, Alsharif KF et al. New insight into the mechanism of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) that induces the mobilization of neutrophils. Hematology 2021; 26: 628–36. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 10.

Dejaco C, Ramiro S, Bond M et al. EULAR recommendations for the use of imaging in large vessel vasculitis in clinical practice: 2023 update. Ann Rheum Dis 2024; 83: 741–51. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 11.

Lötscher F, Pop R, Seitz P et al. Spectrum of Large- and Medium-Vessel Vasculitis in Adults: Neoplastic, Infectious, Drug-Induced, Autoinflammatory, and Primary Immunodeficiency Diseases. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2022; 24: 293–309. [PubMed][CrossRef]