Main findings

Health-related quality of life, measured using the EQ-5D-5L questionnaire, was statistically significantly poorer among patients who had experienced myocardial infarction than in the general population in Norway (EQ-5D-5L index 0.86 vs. 0.88).

Following myocardial infarction, women had a statistically significantly poorer EQ-5D-5L index than men (0.82 vs. 0.87).

Patients who had experienced NSTEMI had a statistically significantly poorer EQ-5D-5L index than those who had experienced STEMI (0.85 vs. 0.88).

Health outcomes following myocardial infarction are typically measured in terms of mortality, risk of relapse and readmission. The patient perspective, in the form of patient-reported health and quality of life, is also important when planning treatment and care (1–3). Patients who have experienced myocardial infarction report poorer health-related quality of life than an assumed healthy population, and a poor quality of life is associated with higher mortality (1–3). Poorer self-reported health-related quality of life is more common among women, older adults and frail adults, as well as those with comorbidities in addition to coronary heart disease (4–7). Several studies have shown that patient-reported data can complement traditional outcome measures in the evaluation of treatment (5, 7, 8).

In Norway, no national studies on self-reported health-related quality of life after myocardial infarction have previously been conducted. The Norwegian Myocardial Infarction Registry is a national medical quality register that includes all patients admitted to Norwegian hospitals with a diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction (ICD 10: I21–I22) (9). Both ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) and non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) as identified on ECG are included. Hospitals are required to report myocardial infarctions to the registry in accordance with the Norwegian Cardiovascular Disease Registry Regulation (10). The coverage rate, measured against the Norwegian Patient Registry, exceeds 90 %, and data quality has been assessed as satisfactory (11–13). Since 2017, the registry has collected patient-reported data three months after discharge from the hospital.

The aim of this article is to describe self-reported data on health-related quality of life among patients with myocardial infarction in Norwegian hospitals in the period 2020–2023 and to compare the results with a Norwegian reference population consisting of a random sample of men and women from the general population.

Material and method

Patients registered in the Norwegian Myocardial Infarction Registry who are discharged to their homes receive a questionnaire 3–4 months after discharge. Digitally active patients receive the questionnaire via the Helsenorge, Digipost or e-Boks app, while the remaining patients receive a paper version in the post (14). A reminder is sent electronically 14 days after the questionnaire is sent, with a completion deadline 14 days after the reminder. Patients who have experienced more than one myocardial infarction within a year only receive the questionnaire after the first one. In this study, we included patients who experienced myocardial infarction in the period 2020–2023.

Measuring health-related quality of life

In the study, we used the generic health-related quality of life questionnaire EQ-5D-5L developed by the EuroQol group (15, 16). The EQ-5D-5L can be used to compare health-related quality of life in a patient population with a general population and with other patient populations. The questionnaire consists of five dimensions/questions (5D) covering mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression (15, 16).

Each dimension has five response options, referred to as levels (5L), which are coded with a numerical value from 1 (indicating no problems) to 5 (extreme problems) (Appendix 1) (5). For the first three questions about mobility, self-care and usual activities, the levels are: 1 = no problems, 2 = slight problems, 3 = moderate problems, 4 = severe problems and 5 = unable to perform usual activities. For the question on pain/discomfort, the five levels range from 1 = no pain or discomfort to 5 = very severe pain or discomfort. For the question on anxiety/depression, the levels range from 1 = not anxious or depressed to 5 = extremely anxious or depressed.

The responses to the five questions form a five-digit number that provides a measure of health status (e.g. '1 - 2–2 - 3–1'). The first digit represents mobility. The health status is scored according to an EQ-5D-5L index value, where each digit in the five responses is assigned a numerical value based on value assessments from a general population sample (16). Current recommendations for scoring the EQ-5D-5L index were followed (17, 18). A score of 1 indicates full health, meaning that the patient's response was 'no problems' to all five questions, while a score of 0 indicates a health status equivalent to death (16). In addition to the five questions, the EQ-5D-5L questionnaire includes a visual analogue scale (EQ-VAS) where the patient rates their health status from 0 to 100, with 100 being the best score (16).

Reference population

The EQ-5D-5L responses from Norwegian myocardial infarction patients were compared with responses from a Norwegian reference population. The reference population consisted of a random sample of 12,790 men and women aged 18–97 years, stratified by age and gender, selected from the National Population Register. In 2019, they received the EQ-5D-5L questionnaire from the Norwegian Institute of Public Health (19). A total of 3200 (25.0 %) patients returned the questionnaire, of whom 3047 answered all questions. The average age was 51 years (standard deviation 21 years) (20).

Results for patients who had experienced myocardial infarction were compared with results from the Norwegian reference population, matched by age group (<50, 50–59, 60–69, 70–79 and > 79 years) and sex (19). Each myocardial infarction patient who completed the questionnaire was matched with a randomly selected person from the reference population of the same sex and within the same age group. Since the number of myocardial infarction patients who completed the questionnaire (n = 19,930) was higher than the reference population (n = 3047), one person from the reference population could be matched with one or more myocardial infarction patients. The proportion of women and men, as well as the age distribution across the various age categories for the reference population, before and after matching with the patients, is shown in Appendix 2.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics are presented as mean values, standard deviations and percentages. In the analyses of the five EQ-5D-5L dimensions, the five levels were combined into two categories: respondents with no problems in the relevant dimension (those who selected response option 1) and respondents who had problems (those who selected response options 2–5). To compare the myocardial infarction patients with the age- and gender-matched Norwegian reference population, the Mantel-Haenszel chi-square test was used. Paired t-tests were used to compare EQ-VAS scores and EQ-5D-5L scores.

Logistic regression was used to examine whether there was variation between different patient groups in the proportion experiencing problems in the various EQ-5D-5L dimensions. Linear regression was used in the analysis of continuous variables. The analyses were adjusted for age, sex and type of myocardial infarction (STEMI or NSTEMI).

Ethics

The compilation and publication of anonymised statistics based on health data in the registry is based on the Norwegian Health Register Act, section 19 (1), cf. the Norwegian Cardiovascular Disease Registry Regulation, section 3 - 1, and does not require prior approval from the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics.

Results

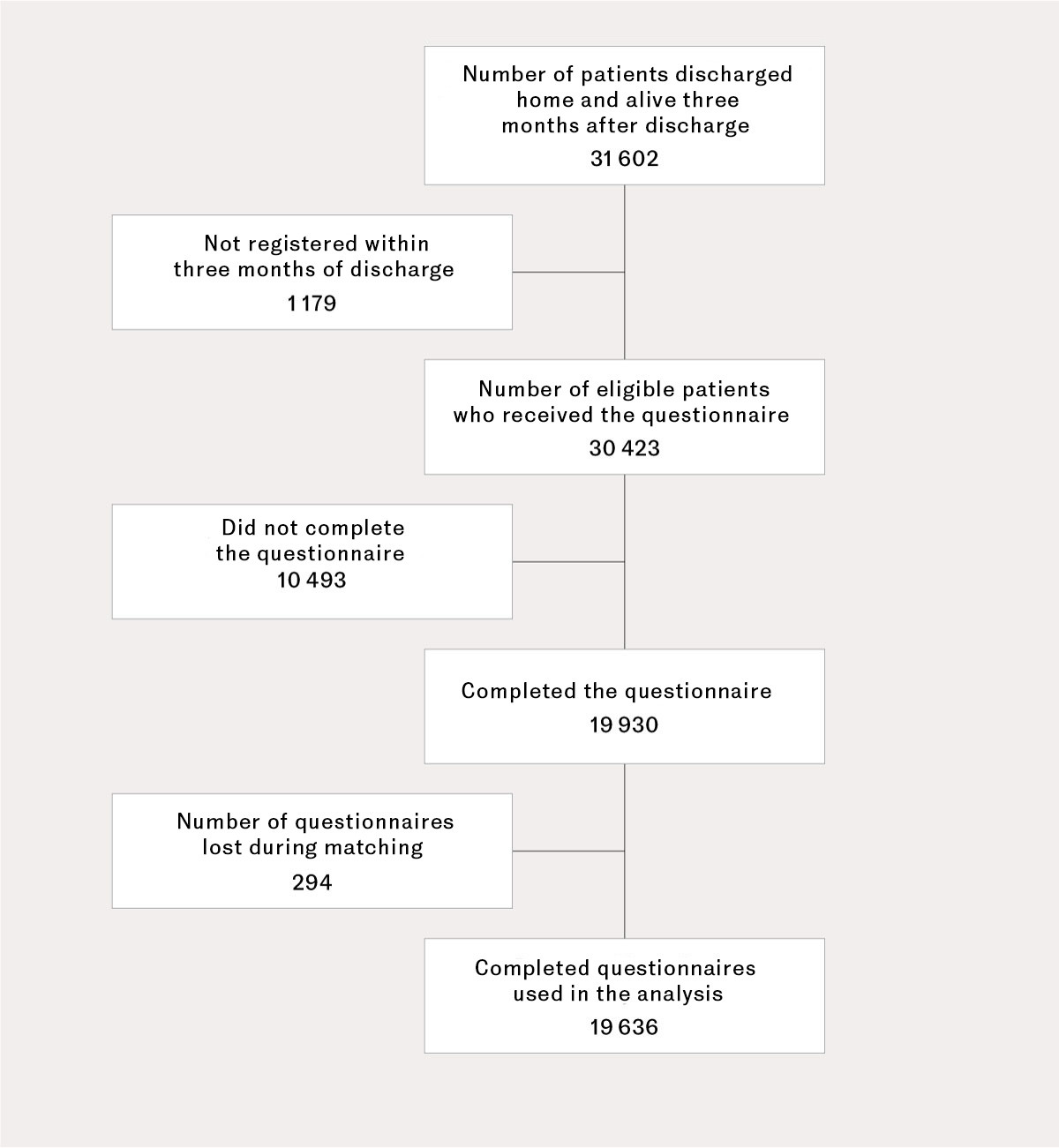

Of the 43,636 patients admitted to hospital with acute myocardial infarction in the period 2020–2023, a total of 31,602 (72 %) were discharged home and were alive 30 days later, thus meeting the criteria to receive the questionnaire.

A total of 1179/31,602 (3.7 %) patients were not registered within the 90-day deadline to receive the questionnaire. Of all the patients who met the criteria to receive the questionnaire, 19,930/31,602 (63 %) completed it (Figure 1). Of these, 294 questionnaires were incomplete and were excluded from the analysis.

Compared to patients who did not complete the questionnaire, those who did were significantly younger and they included a significantly higher proportion of men. Additionally, there were significantly fewer smokers and respondents with comorbidities (Table 1).

Table 1

Characteristics of myocardial infarction patients who completed and did not complete the EQ-5D-5L health-related quality of life questionnaire 3–4 months after discharge home. Data from the Norwegian Myocardial Infarction Registry 2020–23. Amounts are shown as a percentage unless otherwise specified.

| Completed questionnaire | Did not complete questionnaire | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Number (N) | 19 930¹ | 10 493 | |

| Average age (standard deviation) | 67 (12) | 72 (13)² | |

| Men | 73.5 | 64.0² | |

| NSTEMI³ | 63.7 | 74.1² | |

| STEMI⁴ | 32.9 | 22.3² | |

| Previous conditions/illnesses | |||

| Myocardial infarction | 21.3 | 35.8² | |

| Chronic heart failure | 4.2 | 9.5² | |

| Stroke | 4.3 | 9.1² | |

| Treated with percutaneous coronary intervention | 21.4 | 31.6² | |

| Surgery for coronary artery bypass grafting | 7.0 | 11.6² | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 18.0 | 27.1² | |

| Hypertension | 45.9 | 53.0² | |

| Daily smoker | 26.2 | 27.7² | |

¹ Number of patients who completed part or all of the EQ-5D-5L questionnaire

² Significantly different from patients who completed the questionnaire, p < 0.001

³ NSTEMI = non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction on ECG

⁴ STEMI = ST-elevation myocardial infarction on ECG

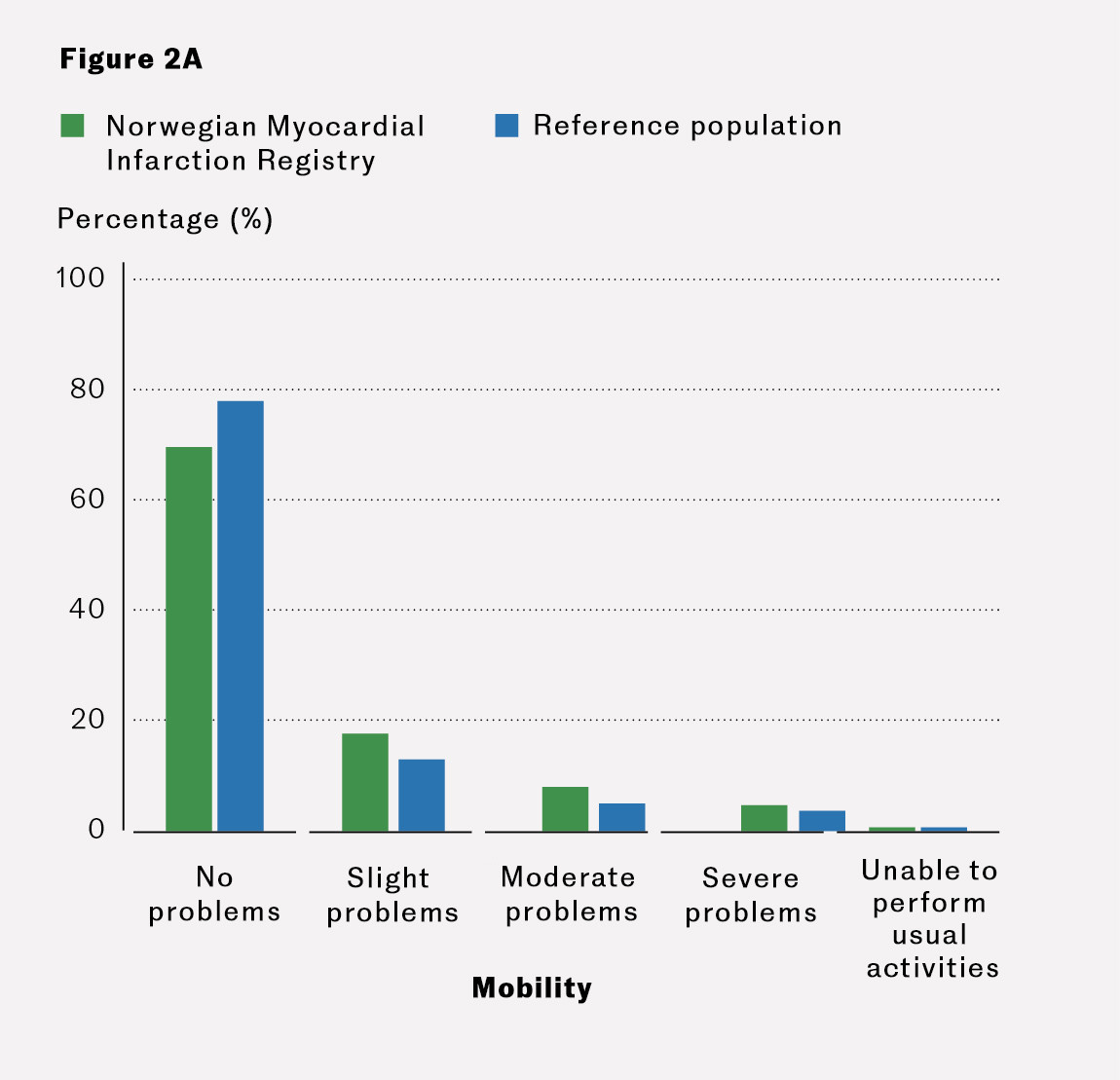

Of the myocardial infarction patients, a total of 32.9 % reported that they had no problems in any of the five EQ-5D-5L dimensions (response option 1), while 66.3 % reported mild to moderate problems (response options 2 and 3) in at least one question, and 10.9 % reported severe to extreme problems (response options 4 and 5) in at least one question (Figure 2).

Compared to the gender- and age-matched reference population, myocardial infarction patients had significantly more problems (ranging from 'slight' to 'severe') with mobility, usual activities and anxiety/depression, but fewer problems with pain/discomfort (p < 0.001). There was no statistically significant difference in self-care between the myocardial infarction patients and the reference population (Figure 2, Table 2). Myocardial infarction patients had significantly lower EQ-5D-5L index scores and EQ-VAS scores than the reference population (Table 2).

Table 2

Percentage of the reference population and patients discharged home after myocardial infarction who reported problems (response options 2–5 in the EQ-5D-5L questionnaire) with performing various activities or experiencing pain/discomfort or anxiety/depression. Mean EQ-5D-5L index and VAS scores. Patients received the questionnaire 3–4 months after their myocardial infarction. Data from the Norwegian Myocardial Infarction Registry 2020–23.

| EQ-5D-5L dimensions | Matched reference population¹ | All patients with myocardial infarction² | P-value | Patients with STEMI³ | Patients with NSTEMI⁴,⁵ | P-value⁶ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 19 636 | N = 19 636 | n = 6 407 | n = 12 570 | ||||

| Percentage that has problems with: | |||||||

| Mobility | 22.0 | 30.3 | < 0.001 | 22.5 | 34.2 | < 0.001 | |

| Self-care | 9.7 | 10.2 | 0.074 | 6.7 | 12.0 | < 0.001 | |

| Usual activities | 22.0 | 36.2 | < 0.001 | 31.4 | 38.7 | < 0.001 | |

| Pain/discomfort | 63.8 | 49.9 | < 0.001 | 45.1 | 52.4 | < 0.001 | |

| Anxiety/depression | 25.4 | 41.3 | < 0.001 | 40.8 | 41.7 | 0.009 | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

| EQ-5D-5L index⁷ | 0.88 (0.16) | 0.86 (0.18) | < 0.001 | 0.88 (0.15) | 0.85 (0.19) | < 0.001 | |

| EQ-VAS score⁷ | 80 (18) | 69 (20) | < 0.001 | 72 (19) | 68 (21) | < 0.001 | |

¹ The reference population was matched for sex and age against all patients with myocardial infarction.

² Questionnaires with missing responses (n = 294) were excluded from the analyses.

³ ST-elevation myocardial infarction on ECG.

⁴ Non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction on ECG.

⁵ Type of myocardial infarction (STEMI or NSTEMI) was unknown for 659 patients.

⁶ Adjusted for age categories and sex.

⁷ The values for the EQ-5D-5L index and EQ-VAS are presented as mean values and standard deviations.

Patients with NSTEMI had significantly more problems (response categories 2–5) with mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression compared to patients with STEMI. Patients with NSTEMI also had a significantly lower EQ-5D-5L index and EQ-VAS scores than those with STEMI (Table 2).

Among myocardial infarction patients, more women than men reported problems across all EQ-5D-5L dimensions, and women had a lower EQ-5D-5L index and EQ-VAS score than men (Table 3). The gender gap was statistically significant for both STEMI and NSTEMI patients after adjusting for age (results not shown).

Table 3

Percentage of myocardial infarction patients who, 3–4 months after discharge home, reported problems (response options 2–5 in the EQ-5D-5L questionnaire) with performing various activities, or pain/discomfort or anxiety/depression. Mean EQ-5D-5L index and VAS scores, distributed by sex (N = 19,636). Data from the Norwegian Myocardial Infarction Registry 2020–23.

| Patients with myocardial infarction¹ | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EQ-5D-5L dimensions | Men | Women | P-value² | |

| Percentage that has problems with: | n = 14 528 | n = 5 108 | ||

| Mobility | 27.5 | 38.2 | < 0.001 | |

| Self-care | 9.3 | 12.9 | < 0.001 | |

| Usual activities | 32.9 | 45.7 | < 0.001 | |

| Pain/discomfort | 47.1 | 57.8 | < 0.001 | |

| Anxiety/depression | 37.6 | 51.7 | < 0.001 | |

|

|

|

|

| |

| EQ-5D-5L index ³ | 0.87 (0.17) | 0.82 (0.19) | < 0.001 | |

| EQ-VAS score ³ | 70 (20) | 65 (21) | < 0.001 | |

¹ Questionnaires with missing responses (n = 294) were excluded from the analyses.

² Adjusted for age categories and type of infarction (STEMI, NSTEMI or unknown).

³ The figures for the EQ-5D-5L index and EQ-VAS score are presented as mean values and standard deviations.

Older patients with myocardial infarction had significantly more problems with mobility and self-care and fewer problems with anxiety/depression. Problems with usual activities and pain were most pronounced among the youngest and oldest patients (Table 4).

Table 4

Percentage of patients (N = 19,636) with myocardial infarction who, 3–4 months after discharge home, reported problems (response options 2–5 in the EQ-5D-5L questionnaire) with performing various activities, or pain/discomfort or anxiety/depression. Mean EQ-5D-5L index and VAS score, categorised by age groups. Data from the Norwegian Myocardial Infarction Registry 2020–23.

| Patients with myocardial infarction¹ | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EQ-5D-5L dimensions | < 50 years | 50 - 59 years | 60 - 69 years | 70 - 79 years | 80+ years | |

| Percentage that has problems with: | n = 1 465 | n = 3 991 | n = 5 899 | n = 5 570 | n = 2 711 | |

| Mobility | 25.3 | 23.4² | 23.8³ | 32.0⁶ | 53,5⁶ | |

| Self-care | 7.6 | 7.3⁵ | 7.3⁶ | 10.4⁷ | 21,7⁴ | |

| Usual activities | 42.0 | 37.0⁴ | 30.4⁴ | 32.5⁴ | 52,1⁴ | |

| Pain/discomfort | 59.2 | 54.1⁴ | 46.1⁴ | 44.8⁴ | 57,6⁴ | |

| Anxiety/depression | 57.6 | 48.4⁴ | 40.0⁴ | 34.7⁴ | 38,3⁴ | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

| EQ-5D-5L index⁸ | 0.83 (0,18) | 0.86 (0.17)⁴ | 0.88 (0.16)⁴ | 0.87 (0.17)⁴ | 0.80 (0.21)⁴ | |

| EQ-VAS score⁸ | 68 (20) | 69 (20)⁴ | 71 (19)⁴ | 70 (21)⁴ | 62 (22)⁴ | |

¹ Questionnaires with missing responses (n = 294) are excluded from the analyses.

² p = 0.099

³ p = 0.047

⁴ p < 0.001

⁵ p = 0.602

⁶ p = 0.379

⁷ p = 0.026, compared to patients < 50 years.

⁸ The figures for the EQ-5D-5L index and EQ-VAS score are the mean value and standard deviation. All p-values are adjusted for sex and type of myocardial infarction.

Discussion

This study shows that patients who have experienced myocardial infarction have less pain but more problems with usual activities, anxiety and depression, as well as poorer general health compared to a Norwegian reference population consisting of a random sample from the general population. Women who have experienced myocardial infarction reported poorer health-related quality of life than men, and patients with NSTEMI had a poorer quality of life than those with STEMI. Physical problems after myocardial infarction increased with age, while the youngest patients reported more anxiety and depression.

Studies in other countries have also shown that patients with myocardial infarction have poorer health-related quality of life than the general population (1–3). However, the patients in this study report, somewhat surprisingly, less general pain/discomfort than the reference population. One possible explanation could be that myocardial infarction, which is a life-threatening condition, alters patients' perception of musculoskeletal pain due to changes in lifestyle and increased physical activity. However, further research is needed in this area.

A higher proportion of the Norwegian reference population reports pain/discomfort compared to reference populations in other countries (21, 22). The proportion of patients with pain/discomfort after myocardial infarction varies between studies (17, 18). Our results align with a registry study from England that includes patients one, six and twelve months after myocardial infarction (17). However, we found that a higher proportion of patients report problems than is found in studies of patients for whom more time had elapsed since their myocardial infarction (18).

As shown in other studies, women report more problems than men after myocardial infarction (1–7), and the difference is greater than in the general population in Norway (19). The gender gap is statistically significant after adjusting for age and type of myocardial infarction.

Age does not appear to have a linear association with health-related quality of life, and the relationship between age and quality of life varies across the different EQ-5D-5L dimensions (19). Our results show that younger patients report more problems with anxiety and depression than older patients. This age difference seems to be greater than in the general population (19). Similar findings have also been reported in other studies (23). This should be noted when following up patients who have experienced myocardial infarction.

Patients with NSTEMI reported poorer health-related quality of life than patients with STEMI. One possible explanation could be that comorbidities are more common among patients with NSTEMI than those with STEMI, and that such conditions impact on quality of life (4, 5).

Over 66 % of patients who had experienced myocardial infarction reported problems in at least one of the EQ-5D-5L dimensions. This is a higher proportion than in an international study of myocardial infarction patients from 25 countries, which showed that about half had at least one problem (9). There was also a lower proportion of problems per dimension than in our study (6). The difference may be due to the international study using the somewhat less sensitive EQ-5D-3L version, which only has three response options (no problems, some problems or extreme problems) (16).

The strength of our study is that a large proportion of myocardial infarction patients from throughout Norway responded to the questionnaire. By matching for age and sex, we were able to compare health-related quality of life in myocardial infarction patients with a reference population consisting of a random sample from the Norwegian population. One of the weaknesses of the study is the low response rate among those defined as the reference population (19). Another weakness is that patients who responded to the questionnaire differ from those who did not respond.

Conclusion

Patients who had experienced myocardial infarction reported poorer health-related quality of life than the general population in Norway but had less pain and discomfort. Women who had experienced myocardial infarction had poorer health-related quality of life than men who had experienced the same. Older myocardial infarction patients had more problems than younger patients. The exception was anxiety and depression, where younger patients reported more problems than older patients. Patients with NSTEMI had more problems than those with STEMI.

The article has been peer-reviewed.

- 1.

Mollon L, Bhattacharjee S. Health related quality of life among myocardial infarction survivors in the United States: a propensity score matched analysis. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2017; 15: 235. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 2.

APPROACH Investigators. Trajectories of Health-Related Quality of Life in Coronary Artery Disease. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2018; 11. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.117.003661. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 3.

Schweikert B, Hunger M, Meisinger C et al. Quality of life several years after myocardial infarction: comparing the MONICA/KORA registry to the general population. Eur Heart J 2009; 30: 436–43. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 4.

Munyombwe T, Dondo TB, Aktaa S et al. Association of multimorbidity and changes in health-related quality of life following myocardial infarction: a UK multicentre longitudinal patient-reported outcomes study. BMC Med 2021; 19: 227. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 5.

Munyombwe T, Hall M, Dondo TB et al. Quality of life trajectories in survivors of acute myocardial infarction: a national longitudinal study. Heart 2020; 106: 33–9. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 6.

Pocock S, Brieger DB, Owen R et al. Health-related quality of life 1-3 years post-myocardial infarction: its impact on prognosis. Open Heart 2021; 8. doi: 10.1136/openhrt-2020-001499. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 7.

Rasmussen AA, Fridlund B, Nielsen K et al. Gender differences in patient-reported outcomes in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2022; 21: 772–81. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 8.

Boulding W, Glickman SW, Manary MP et al. Relationship between patient satisfaction with inpatient care and hospital readmission within 30 days. Am J Manag Care 2011; 17: 41–8. [PubMed]

- 9.

Jortveit J, Govatsmark RE, Digre TA et al. Hjerteinfarkt i Norge i 2013. Tidsskr Nor Legeforen 2014; 134: 1841–6. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 10.

Helse- og omsorgsdepartementet. FOR-2011-12-16-1250. Forskrift om innsamling og behandling av helseopplysninger i Nasjonalt register over hjerte- og karlidelser (Hjerte- og karregisterforskriften). https://lovdata.no/dokument/SF/forskrift/2011-12-16-1250?q=hjerte-%20og%20karregister Accessed 29.1.2025.

- 11.

Govatsmark RE, Sneeggen S, Karlsaune H et al. Interrater reliability of a national acute myocardial infarction register. Clin Epidemiol 2016; 8: 305–12. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 12.

Govatsmark RES, Janszky I, Slørdahl SA et al. Completeness and correctness of acute myocardial infarction diagnoses in a medical quality register and an administrative health register. Scand J Public Health 2020; 48: 5–13. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 13.

Norsk hjerteinfarktregister. Årsrapport 2021. https://www.kvalitetsregistre.no/4acc0c/siteassets/dokumenter/arsrapporter/hjerteinfarktregisteret/arsrapport-2021-norsk-hjerteinfarktregister.pdf Accessed 29.1.2025.

- 14.

Overordnet skisse for ePROM papir (PIPP). https://eprom.hemit.org/Overordnetskisse%20papir Accessed 29.1.2025.

- 15.

EuroQol Group. EQ-5D-5L Spørreskjema om helse. Norsk versjon, for Norge. https://www.oslo-universitetssykehus.no/491638/contentassets/6f20a068a8814035861e9e7a4de77600/dokumenter/eq-5d-5l.pdf Accessed 29.1.2025.

- 16.

Oemar MJB. EQ-5D-5L User Guide. Basic information on how to use the EQ-5D-5L instrument, versjon 2.0 2013. https://www.unmc.edu/centric/_documents/EQ-5D-5L.pdf Accessed 29.1.2025.

- 17.

Dondo TB, Munyombwe T, Hall M et al. Sex differences in health-related quality of life trajectories following myocardial infarction: national longitudinal cohort study. BMJ Open 2022; 12. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-062508. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 18.

Krishnamurthy SN, Pocock S, Kaul P et al. Comparing the long-term outcomes in chronic coronary syndrome patients with prior ST-segment and non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: findings from the TIGRIS registry. BMJ Open 2023; 13. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-070237. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 19.

Garratt AM, Hansen TM, Augestad LA et al. Norwegian population norms for the EQ-5D-5L: results from a general population survey. Qual Life Res 2022; 31: 517–26. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 20.

Alm-Kruse K, Gjerset GM, Tjelmeland IBM et al. How do survivors after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest perceive their health compared to the norm population? A nationwide registry study from Norway. Resusc Plus 2024; 17. doi: 10.1016/j.resplu.2023.100549. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 21.

Szende Am Janssen B, Cabases J. Self-Reported Population Health: An International Perspective based on EQ-5D. New York, NY: Springer Open, 2014.

- 22.

Swedish Quality Register (SWEQR) Study Group. Experience-based health state valuation using the EQ VAS: a register-based study of the EQ-5D-3L among nine patient groups in Sweden. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2023; 21: 34. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 23.

Khan Z, Musa K, Abumedian M et al. Prevalence of Depression in Patients With Post-Acute Coronary Syndrome and the Role of Cardiac Rehabilitation in Reducing the Risk of Depression: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2021; 13. doi: 10.7759/cureus.20851. [PubMed][CrossRef]

Det mangler noe opplysninger om pasientene har deltatt på hjerterehabilitering etter infarktet. Har dette eventuelt gitt noe bedre opplevelse?