Main findings

A high proportion of categorical registry variables that could be extracted directly from the patient record text without interpretation had been correctly registered.

This proportion was lower for categorical variables based on an interpretation of the patient record text.

The proportion of correctly registered entries was low for some time variables.

In Norway, 61 national medical quality registries have been established, based on diagnoses, procedures or services (1). The main purpose of these registries is to contribute to better patient treatment (1, 2). They are also used for research and administration. In many medical fields, the national quality registries are the most important sources of systematic information on patient groups, treatment and treatment outcomes (1, 3).

The Norwegian Myocardial Infarction Registry is a nationwide, personally identifiable medical quality registry for patients admitted to Norwegian hospitals with a diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction (ICD-10 diagnosis codes I21 and I22). Norwegian hospitals are required to register all patients admitted with a myocardial infarction (4). Registration typically takes place after the patient has been discharged. The registry has a coverage rate of approximately 90 % compared to the Norwegian Patient Register. At each hospital, a doctor has local responsibility for ensuring that patients are registered, while the personnel entering data into the register vary between hospitals, consisting mainly of nurses, but also medical secretaries and doctors.

The value of a quality registry depends on the quality of the data entered (5). Data quality can be measured by various factors, such as coverage rate, consistency and accuracy. Accuracy refers to the extent to which the values entered for a variable reflect reality (6, 7). This is typically assessed by counting the number of correctly classified entries, as defined by a reference standard, and dividing this number by the total number of entries.

There are few published studies examining the accuracy of data registered in Norwegian medical quality registries. Two studies, from the Norwegian Myocardial Infarction Registry and the Norwegian Stroke Register respectively, concluded that the variables examined showed close agreement between initial registration and subsequent registration by experienced nurses (8, 9). However, these studies did not examine the consistency or accuracy of individual response alternatives. Differences in the proportion of correctly registered data for various response alternatives are also a relevant measure of data quality in a registry, but they do not appear in variable-level calculations, as these provide an average across all response alternatives.

Most electronic patient record systems used in Norway consist of unstructured free-text records. This leads to variation in form and content, making it more difficult to extract and transfer information from patient records to registries. The quality of variables that need to be based on interpretations of patient record text may be lower than that of variables based on information that can be taken more or less directly from the patient record (10).

The aim of this study was to examine a sample of registry variables in the Norwegian Myocardial Infarction Registry and their response alternatives, as well as to calculate the proportion of correctly registered variables compared to a reference standard.

Material and method

Patient sample

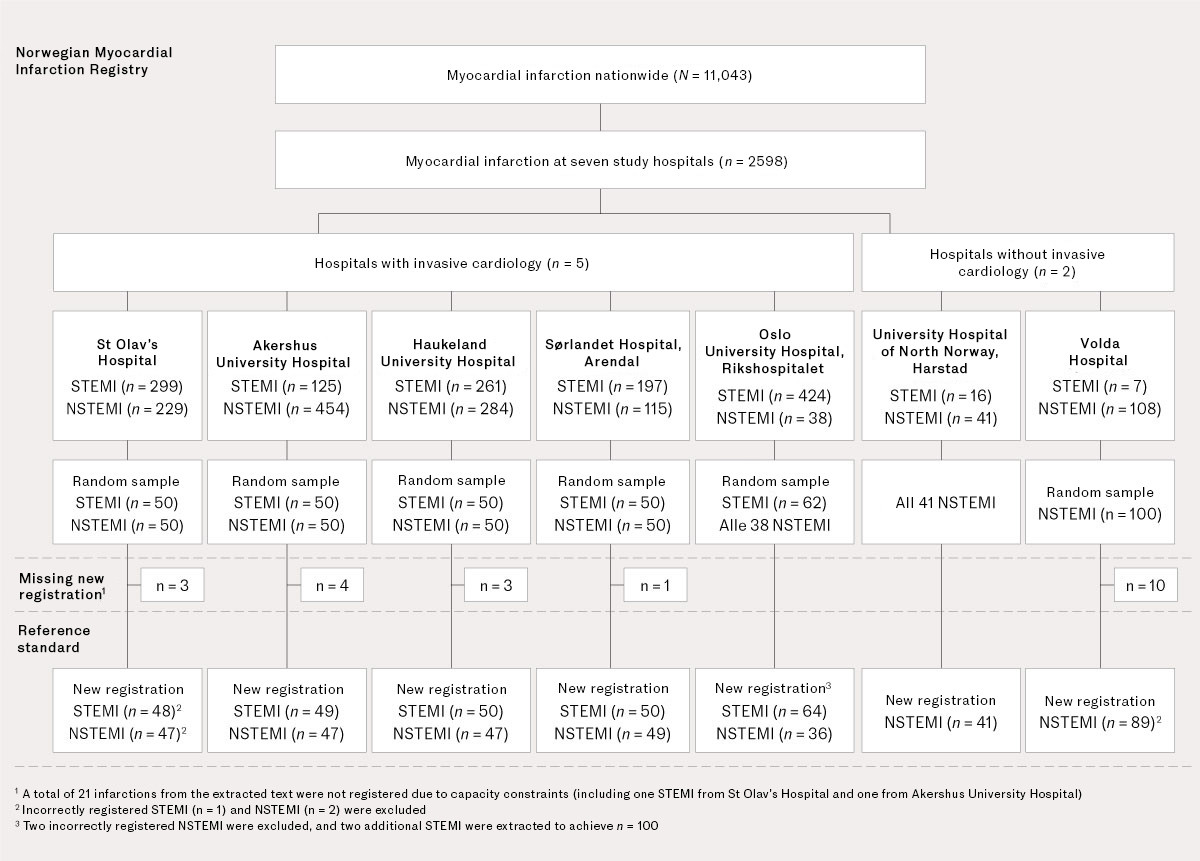

Two hospitals with and five hospitals without invasive cardiology participated in the study. These were the same seven hospitals represented by a member of the clinical advisory board (doctor) at the Norwegian Myocardial Infarction Registry. Using the statistical software RStudio (Posit Software, PBC, Boston, MA, USA) and the 'Sample()' function, a total of 641 cases were randomly selected from 2598 registered myocardial infarctions at the participating hospitals in 2020 (Figure 1).

No calculation of statistical power or sample size was applied for the sample; the starting point was that each participating hospital would contribute n = 100. From hospitals with invasive cardiology, 50 myocardial infarctions with ST elevation (STEMI) and 50 myocardial infarctions without ST elevation (NSTEMI) were selected. Half of the NSTEMI infarctions were selected from those registered with at least one 'Yes' for six variables related to clinical instability. This was to ensure a basis for evaluating this subgroup. The two hospitals without invasive cardiology, which therefore had very few STEMI patients, only contributed with NSTEMI infarctions (Figure 1). An encrypted patient list was then sent to the study doctor at each hospital.

Reference standard

Seven doctors, who were specialists in cardiology or specialty registrars in cardiology or internal medicine, reviewed the patient records and recorded the study variables in a database identical to the registry's ordinary production database. The study doctors did not have access to previous information registered about the patients. Their entries in the study database constituted the reference standard for calculating the proportion of correctly registered variables.

Study variables

Twenty-three out of 80 variables in the Norwegian Myocardial Infarction Registry were examined, including 10 study variables covering dominant symptoms, whether a diagnostic ECG was performed, infarction type and subclassification, smoking status, thrombolysis treatment, invasive coronary investigation (with findings and treatment), and myocardial infarction as a complication. Six study variables relating to clinical instability in NSTEMI included persistent/recurring/new chest pain, suspicion of new-onset ischemia on echocardiogram, dynamic ST-T changes in ECG, acute myocardial infarction/pulmonary congestion/oedema, cardiogenic shock and ventricular tachycardia/fibrillation/asystole. Seven study variables indicated the timing of symptom onset, first assessment by healthcare personnel (hereafter referred to as first medical contact), diagnostic ECG (STEMI patients), admission to hospital, thrombolysis and coronary investigation and treatment.

The explanations for the study variables were the same as in the Myocardial Infarction Registry's user manual (the study doctor used an abridged version with the 23 study variables), see Appendix 1. For the response alternatives for each variable, see Appendix 2.

The patient data that formed the basis for the variables were divided into three categories, based on how they were registered in the patient records:

1) Categorical variables that could easily be read from the text of the patient record and entered directly into the database without interpretation (Table 1).

Table 1

Proportion of correctly registered categorical variables and response alternatives in the Norwegian Myocardial Infarction Registry at seven Norwegian hospitals in 2020 for variables extracted without interpretation from patient records. ECG: electrocardiography; NSTEMI: non-ST elevation myocardial infarction; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI: ST elevation myocardial infarction.

| Variables and response alternatives¹ | Entries (n) | Percentage (%) of correctly registered variables compared with reference standard² |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Dominant symptoms | 617 | 92.2 (569/617) |

| Chest pain | 96.3 (501/520) | |

| Dyspnoea | 71.1 (27/38) | |

| Circulatory failure | 79.2 (19/24) | |

| Other | 64.7 (22/34) | |

| Unknown | 0.0 (0/1) | |

| 2. Where was the diagnostic ECG performed (for STEMI) ³ | 244 | 90.2 (220/244) |

| Pre-hospital | 94.5 (206/218) | |

| Hospital | 58.3 (14/24) | |

| Unknown | 0.0 (0/2) | |

| 3. Infarction type ⁴ | 588 | 93.2 (548/588) |

| STEMI | 94.6 (244/258) | |

| NSTEMI | 96.2 (304/316) | |

| Unknown | 0.0 (0/14) | |

| 4. Subclassification of infarction | 617 | 94.5 (583/617) |

| Type 1 | 97.7 (543/556) | |

| Type 2 | 75.5 (40/53) | |

| Type 3 | n/a | |

| Type 4a | 0.0 (0/1) | |

| Type 4b | n/a | |

| Uknown | 0.0 (0/7) | |

| 5. Smoking status | 617 | 87.4 (539/617) |

| Never | 86.9 (159/183) | |

| Smoker | 94.3 (149/158) | |

| Ex-smoker | 91.7 (199/217) | |

| Unknown | 54.2 (32/59) | |

| 6. Thrombolysis treatment | 617 | 99.7 (615/617) |

| Pre-hospital | 92.9 (26/28) | |

| Hospital | 100 (1/1) | |

| No | 100 (588/588) | |

| 8. PCI | 617 | 96.6 (596/617) |

| Yes | 96.2 (356/370) | |

| No | 97.2 (240/247) | |

| 10. Invasive coronary angiography without PCI | 617 | 97.1 (599/617) |

| Yes | 89.2 (58/65) | |

| No | 98.0 (541/552) | |

| 12. Findings from coronary angiogram/PCI | 428 | 91.8 (575/428) |

| Normal | 87.5 (21/24) | |

| Multivessel disease/main trunk | 94.9 (166/175) | |

| Single-vessel disease | 90.0 (206/229) | |

| Unknown | n/a |

¹ See Appendix 1 for a numbered overview of study variables.

² The numbers in parentheses represent the number of correctly registered entries in the Norwegian Myocardial Infarction Registry divided by the number of entries in the reference standard. The reference standard was a new registration by the study doctor (a specialist in cardiology or specialty registrar in cardiology or internal medicine).

³ Applies to myocardial infarctions where there was agreement between the Norwegian Myocardial Infarction Registry and the reference standard regarding STEMI/NSTEMI diagnosis.

⁴ Applies to myocardial infarctions where there was agreement between the Norwegian Myocardial Infarction Registry and the reference standard regarding whether an ECG was performed.

2) Categorical variables where data extraction and categorisation were an interpretation of the patient record text (Table 2).

Table 2

Proportion of correctly registered categorical registry variables and response alternatives in the Norwegian Myocardial Infarction Registry at seven Norwegian hospitals in 2020 for variables that were an interpretation of the patient record text. ECG: electrocardiography; NSTEMI: non-ST elevation myocardial infarction.

| Variables and response alternatives¹ | Entries | Percentage (%) of correctly registered variables compared with reference standard² |

|---|---|---|

| 13. Persistent/recurring/new chest pain | 302³ | 74.5 (225/302) |

| Yes | 56.9 (41/72) | |

| No | 80.0 (184/230) | |

| 14. Echocardiogram shows suspected new-onset ischemia | 303 | 70.0 (212/303) |

| Yes | 69.5 (66/95) | |

| No | 78.1 (132/169) | |

| Inconclusive findings | 38.5 (5/13) | |

| Not performed | 34.6 (9/26) | |

| 15. Dynamic ST-T changes in ECG | 302 | 77.2 (233/302) |

| Yes | 32.7 (17/52) | |

| No | 87.1 (216/248) | |

| Unknown | n/a | |

| 16. Acute myocardial infarction/pulmonary congestion/oedema | 303 | 89.4 (271/303) |

| Yes | 47.5 (19/40) | |

| No | 95.8 (252/263) | |

| 17. Cardiogenic shock | 303 | 95.4 (289/303) |

| Yes | 20.0 (2/10) | |

| No | 98.3 (287/292) | |

| 18. Ventricular tachycardia/fibrillation/asystole | 303 | 97.0 (294/303) |

| Yes | 62.5 (5/8) | |

| No | 98.3 (289/294) | |

| 19. Myocardial infarction as a complication | 617 | 84.9 (524/617) |

| Yes | 59.8 (64/107) | |

| No | 90.4 (460/509) | |

| Unknown | n/a |

¹ See Appendix 1 for a numbered overview of study variables. Variable nos. 13–18 were included in the assessment of clinical instability in NSTEMI.

² The numbers in parentheses represent the number of correctly registered entries in the Norwegian Myocardial Infarction Registry divided by the number of entries in the reference standard. The reference standard was a new registration by the study doctor (a specialist in cardiology or specialty registrar in cardiology or internal medicine).

³ One NSTEMI infarction was missing for variable nos. 13 and 15.

3) Continuous time variables (Table 3).

Table 3

Agreement in registration for continuous time variables in the Norwegian Myocardial Infarction Registry in 2020 at seven Norwegian hospitals, divided by infarction type. ECG: electrocardiography; NSTEMI: non-ST elevation myocardial infarction; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI: ST elevation myocardial infarction.

| Time variables for each infarction type¹ | Agreement in entries in the Norwegian Myocardial Infarction Registry and the reference standard,²n (%) | Time difference between entries in the Norwegian Myocardial Infarction Registry and the reference standard,²n (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STEMI (n = 244) | Missing entries in the Norwegian Myocardial Infarction Registry or the reference standard,²n (%) | Registered as 'unknown' | Registered with same time | < 10 min | 11–29 min | > 30 min | |

| 20. Symptom onset | 23 (9) | 16 (7) | 156 (64) | 8 (3) | 19 (8) | 22 (9) | |

| 21. First medical contact | 45 (18) | 19 (8) | 130 (53) | 22 (9) | 18 (7) | 10 (4) | |

| 22. Diagnostic ECG | 27 (11) | 7 (3) | 124 (51) | 35 (14) | 27 | 24 | |

| 23. Admission to hospital | 10 (4) | n/a | 116 (48) | 84 (34) | 18 (7) | 16 (7) | |

| 9. PCI (n = 213) | n/a | n/a | 178 (84) | 16 (8) | 10 (5) | 9 (4) | |

| 11. Invasive angiography without PCI (n = 10) | n/a | n/a | 10 (100) | n/a | n/a | n/a | |

| NSTEMI (n = 304) | |||||||

| 20. Symptom onset | 104 (34) | 51 (21) | 121 (40) | 3 (1) | 12 (4) | 13 (4) | |

| 21. First medical contact | 62 (20) | 22 (7) | 139 (46) | 25 (8) | 29 | 27 (9) | |

| 23. Admission to hospital | 5 (2) | n/a | 158 (52) | 89 (29) | 24 (8) | 28 (9) | |

| 9. PCI (n = 111) | n/a | n/a | 99 (89) | 3 (3) | 1 (1) | 8 (7) | |

| 11. Invasive angiography without PCI (n = 34) | n/a | n/a | 28 (82) | 5 (15) | n/a | 1 (3) | |

¹ See Appendix 1 for a numbered list of study variables.

² The reference standard was a new registration by the study doctor (a specialist in cardiology or specialty registrar in cardiology or internal medicine).

Statistical analyses

The percentage (%) of correctly registered variables was calculated as the number of correctly registered entries in the Norwegian Myocardial Infarction Registry compared to the reference standard, divided by the total number of entries. See an example of a variable with three response alternatives in Table 4.

Table 4

Example of entries in the Norwegian Myocardial Infarction Registry from seven Norwegian hospitals in 2020. The table shows the percentage of correct entries for a registry variable with three response alternatives compared to the reference standard. The reference standard was a new registration by the study doctor (a specialist in cardiology or specialty registrar in cardiology or internal medicine).

| Complications at this hospital: myocardial infarction¹ | Reference standard | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | Unknown | |||

| Norwegian Myocardial Infarction Registry | No | 460 | 43 | 0 | 503 |

| Yes | 46 | 64 | 1 | 111 | |

| Unknown | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | |

| Total | 509 | 107 | 1 | 617 | |

| Percentage of correct entries | 90 % | 60 % | 0 % | 85 % | |

¹ Variable no. 19 (see Appendix 2).

The percentage (%) of correct entries for each response alternative was calculated as the number of correctly registered entries in the Norwegian Myocardial Infarction Registry, divided by the number of entries with the same response alternative in the reference standard, as shown in the example in Table 4. The example illustrates that a high proportion of correctly registered variables (in this case 85 %), can mask a low percentage of correctly registered entries for one or more response alternatives – in this case 60 % correctly registered under 'Yes'.

Ethics and data protection

The Norwegian Institute of Public Health was the data controller, and St Olav's Hospital, Trondheim University was the data processor for the Norwegian Myocardial Infarction Registry. In accordance with the Norwegian Cardiovascular Disease Registry Regulation (4), the Norwegian Institute of Public Health is responsible for ensuring that the data processed in the registry is accurate, relevant and necessary. The study was conducted in accordance with the data processing agreement between the Norwegian Institute of Public Health and St Olav's Hospital, which requires the data processor to perform routine comparisons of the registry's content with the information in the patient records. It was not therefore deemed necessary to obtain patient consent.

Results

Of the 641 myocardial infarctions in the extracted data, 21 were missing in the reference standard because the study doctor did not manage to re-register them (Figure 1). An additional three infarctions were excluded due to incorrect registration, leaving 617 infarctions included in the reference standard (Figure 1). The average age (standard deviation) was 70 (13) years, and 71 % were men. The number of entries for each response alternative for the 23 study variables in the Norwegian Myocardial Infarction Registry and in the reference standard is summarised in Appendix 2, along with the percentage of correct entries for variables and response alternatives.

Table 1 shows the proportion of correctly registered variables and response alternatives in the Norwegian Myocardial Infarction Registry compared to the reference standard for categorical variables that could be retrieved from the patient records without interpretation. The overall percentage of correct entries was > 90 % for most variables, while for each response alternative it varied between 54 % and 100 %. The location for diagnostic ECG and the subclassification of infarction were two registry variables with a high percentage of correct entries (90 % and 95 %, respectively) but also a low percentage for some response alternatives (58 % for 'ECG performed at the hospital' and 76 % for 'Type 2 infarction').

Table 2 shows the proportion of correctly registered variables and response alternatives in the Norwegian Myocardial Infarction Registry compared to the reference standard for categorical variables based on the interpretation of patient record text. The proportion of correctly registered entries for the response alternative 'Yes' for six variables on clinical instability in NSTEMI ranged from 20 % for cardiogenic shock to 70 % for suspected new-onset ischemia on echocardiogram. The percentage of correct entries for the response alternative 'No' ranged from 78 % for new-onset ischemia on echocardiogram to 98 % for cardiogenic shock and ventricular tachycardia/ventricular fibrillation/asystole. For the variable 'Myocardial infarction as a complication', 85 % were correctly registered for both types of infarction, while the percentage for the response alternatives 'Yes' and 'No' were 60 % and 90 %, respectively.

Table 3 summarises the results for continuous time variables. The percentage where the same time was registered in the Norwegian Myocardial Infarction Registry and the reference standard, or where there was agreement that the time was not registered in the patient record, ranged from 48 % for the time of admission to 100 % for the time of angiography in STEMI. The percentage of correct entries was higher when a time difference of up to 10 minutes was considered a correct time indication.

Discussion

This study shows that data quality, assessed as the proportion of correctly registered entries in the Myocardial Infarction Registry, varied. Variables and response alternatives where the data extraction was based on an interpretation of the patient record text had a lower proportion of correct entries than variables that could be read directly from the patient record without interpretation. Additionally, some important time variables had a low proportion of correctly registered times.

We found a high proportion of correctly registered categorical variables that could be read directly from the patient record and extracted to the database without interpretation, such as 'Type of myocardial infarction', 'Dominant symptom' and 'Smoking status'. However, the study showed significant discrepancies between the Norwegian Myocardial Infarction Registry and the reference standard for the variable 'Myocardial infarction as a complication' and for six variables describing clinical instability in NSTEMI. An earlier inter-rater study of the Norwegian Myocardial Infarction Registry also had similar findings (9). Consequently, and in consultation with the advisory board, these six variables are no longer included in the Norwegian Myocardial Infarction Registry.

As a general rule, it is doctors who write the notes in patient records, and given the free-text format and absence of structure in electronic patient records, form and content can vary for patients with myocardial infarction. Consequently, the information may therefore be interpreted and categorised differently by various occupational groups, and the competence of the person registering the information can impact on data quality (11). It is our view that registry variables based on an interpretation of free text from patient records should, therefore, be used with caution in quality improvement and research.

To assess the quality of treatment for myocardial infarction, particularly in STEMI patients, it is crucial that key moments in the patient pathway are correctly registered. Even when we categorised time differences of up to 10 minutes as correctly registered, the proportion of correct times for symptom onset, first medical contact and admission to hospital was still no higher than 70–82 %.

The electronic patient record systems often lack definitions for various time points in patient pathways, and it is unclear who is responsible for registering these. This can result in, for example, the admission time being based on other registered times, such as the ordering of a blood test or the date of an ECG. Ambulance records contain information on key time points, and their suitability as a primary source should be evaluated (10).

Strengths of the study included the participation of doctors with expertise in cardiology, representation from all health regions, and the study database, which allowed simulation of typical registration practices. A limitation of having the study doctors define the reference standard was their variation in cardiology expertise and knowledge of the registry and registration practices. Overall, the results may therefore reflect consistency rather than accuracy.

The method used in the study is suitable for examining data quality on variables with more than two response alternatives, in the same way as specific agreement (12, 13). The analysis for each response alternative provides more details and can offer more clinically relevant information about data quality than traditional analyses of accuracy or agreement (where data quality for a variable is reported as an average for all response alternatives) (12, 13).

Conclusion

Variables that could be extracted from the patient record text and transferred without interpretation mostly had a high proportion of correct entries per variable and response alternative. However, a lower proportion of correct entries was observed for variables where data extraction and categorisation were based on an interpretation of unstructured patient record text, as well as for certain time variables.

The article has been peer-reviewed.

- 1.

Stensland E, Skau P. Medisinske kvalitetsregistere i Norge. Nor Epidemiol 2023; 31: 3–8. [CrossRef]

- 2.

Helsedirektoratet. Kvalitet og kvalitetsindikatorer. https://www.helsedirektoratet.no/statistikk/kvalitetsindikatorer/kvalitet-og-kvalitetsindikatorer#hvaerenkvalitetsindikator Accessed 8.5.2023.

- 3.

Senter for klinisk dokumentasjon og evaluering (SKDE). Registeroversikt: Nasjonalt servicemiljø for medisinske kvalitetsregistre. https://www.kvalitetsregistre.no/registeroversikt Accessed 25.7.2023.

- 4.

Helse- og omsorgsdepartementet. FOR-2011-12-16-1250. Forskrift om innsamling og behandling av helseopplysninger i Nasjonalt register over hjerte- og karlidelser (Hjerte- og karregisterforskriften). https://lovdata.no/dokument/SF/forskrift/2011-12-16-1250/KAPITTEL_1#%C2%A71-2 Accessed 15.4.2024.

- 5.

Senter for klinisk dokumentasjon og evaluering (SKDE). Datakvalitet: Nasjonalt servicemiljø for medisinske kvalitetsregistre. https://www.kvalitetsregistre.no/datakvalitet Accessed 28.12.2022.

- 6.

Senter for klinisk dokumentasjon og evaluering (SKDE). Dimensjoner av datakvalitet: Nasjonalt servicemiljø for medisinske kvalitetsregistre. https://www.kvalitetsregistre.no/node/38 Accessed 24.6.2024.

- 7.

Arts DG, De Keizer NF, Scheffer GJ. Defining and improving data quality in medical registries: a literature review, case study, and generic framework. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2002; 9: 600–11. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 8.

Varmdal T, Ellekjær H, Fjærtoft H et al. Inter-rater reliability of a national acute stroke register. BMC Res Notes 2015; 8: 584. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 9.

Govatsmark RE, Sneeggen S, Karlsaune H et al. Interrater reliability of a national acute myocardial infarction register. Clin Epidemiol 2016; 8: 305–12. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 10.

Silsand L, Severinsen GH, Ellingsen G et al. Structuring Electronic Patient Record Data, a Smart Way to Extract Registry Information? Reports of the European Society for Socially Embedded Technologies 2019; 3. doi: 10.18420/ihc2019_009. [CrossRef]

- 11.

Meyer B, Shiban E, Albers LE et al. Completeness and accuracy of data in spine registries: an independent audit-based study. Eur Spine J 2020; 29: 1453–61. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 12.

Lydersen S. Positivt og negativt samsvar. Tidsskr Nor Legeforen 2018; 138. doi: 10.4045/tidsskr.17.0963. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 13.

de Vet HCW, Mullender MG, Eekhout I. Specific agreement on ordinal and multiple nominal outcomes can be calculated for more than two raters. J Clin Epidemiol 2018; 96: 47–53. [PubMed][CrossRef]