Introduction of a high dependency unit at a large paediatric and adolescent medicine department

MAIN FINDINGS

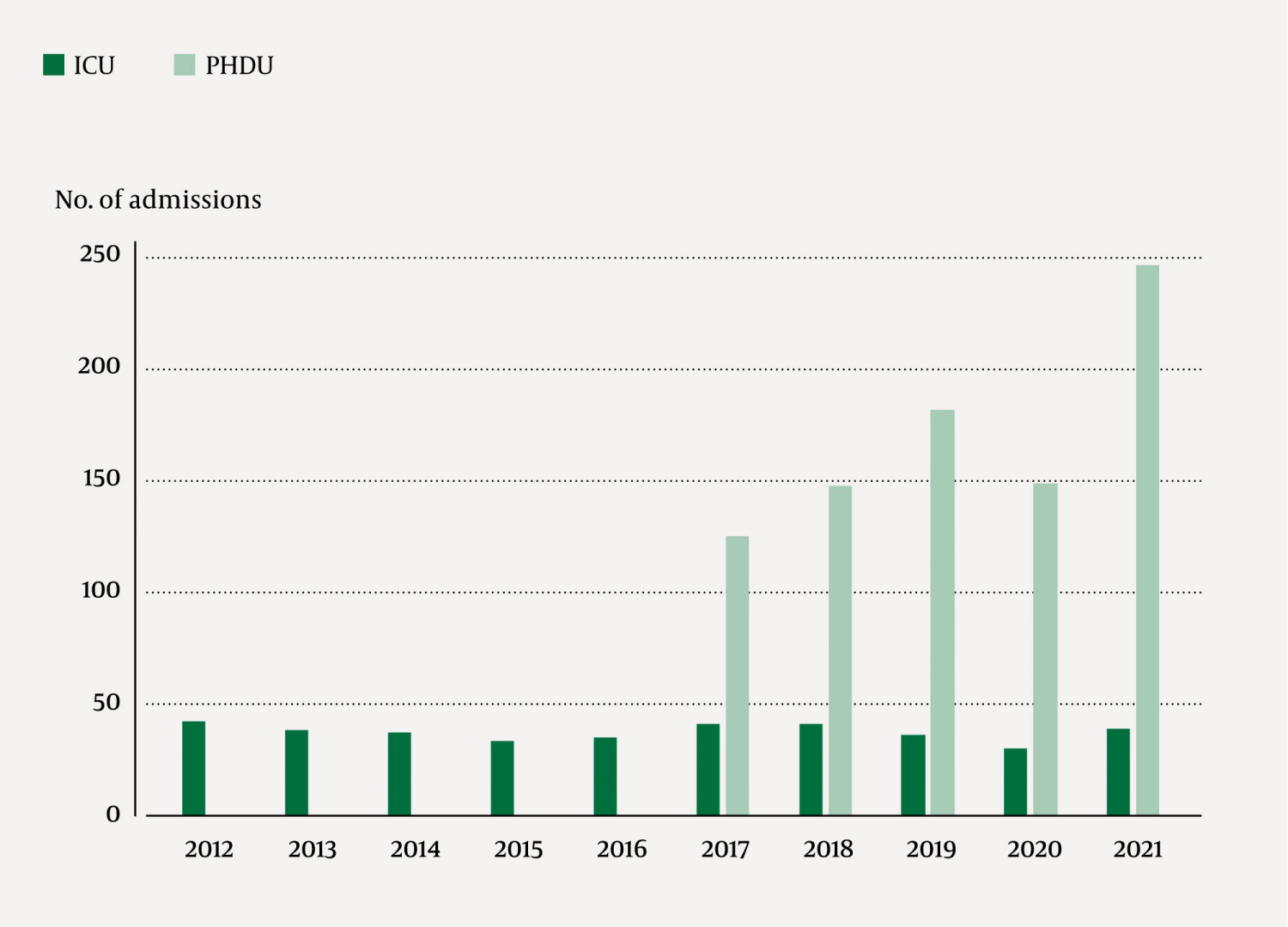

After the establishment of a paediatric high dependency unit (PHDU), the proportion of admissions per year relative to all paediatric admissions has increased from 3.5 % to 7.6 %, while the proportion of admissions to the intensive care unit (ICU) has remained stable (1 %).

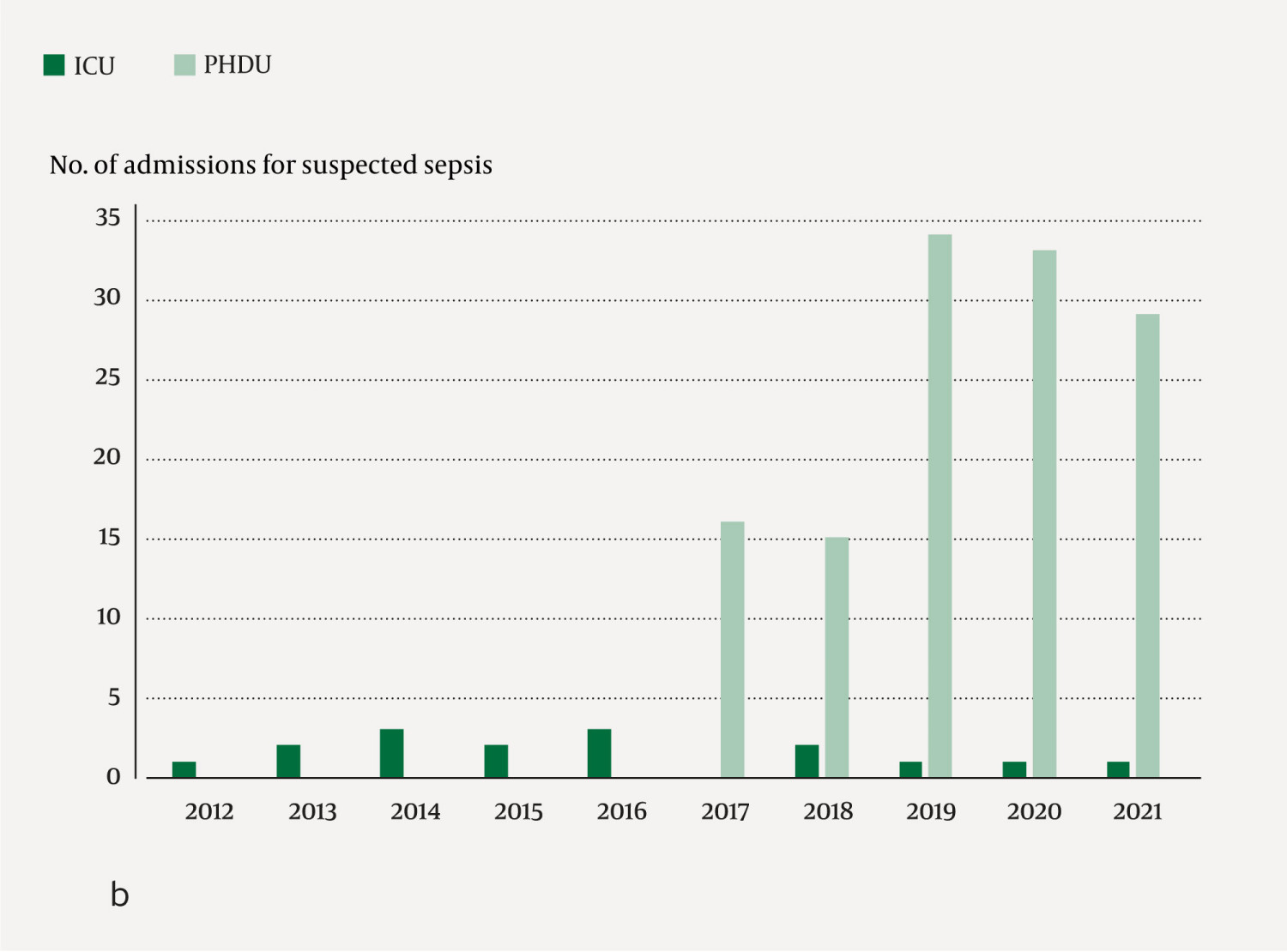

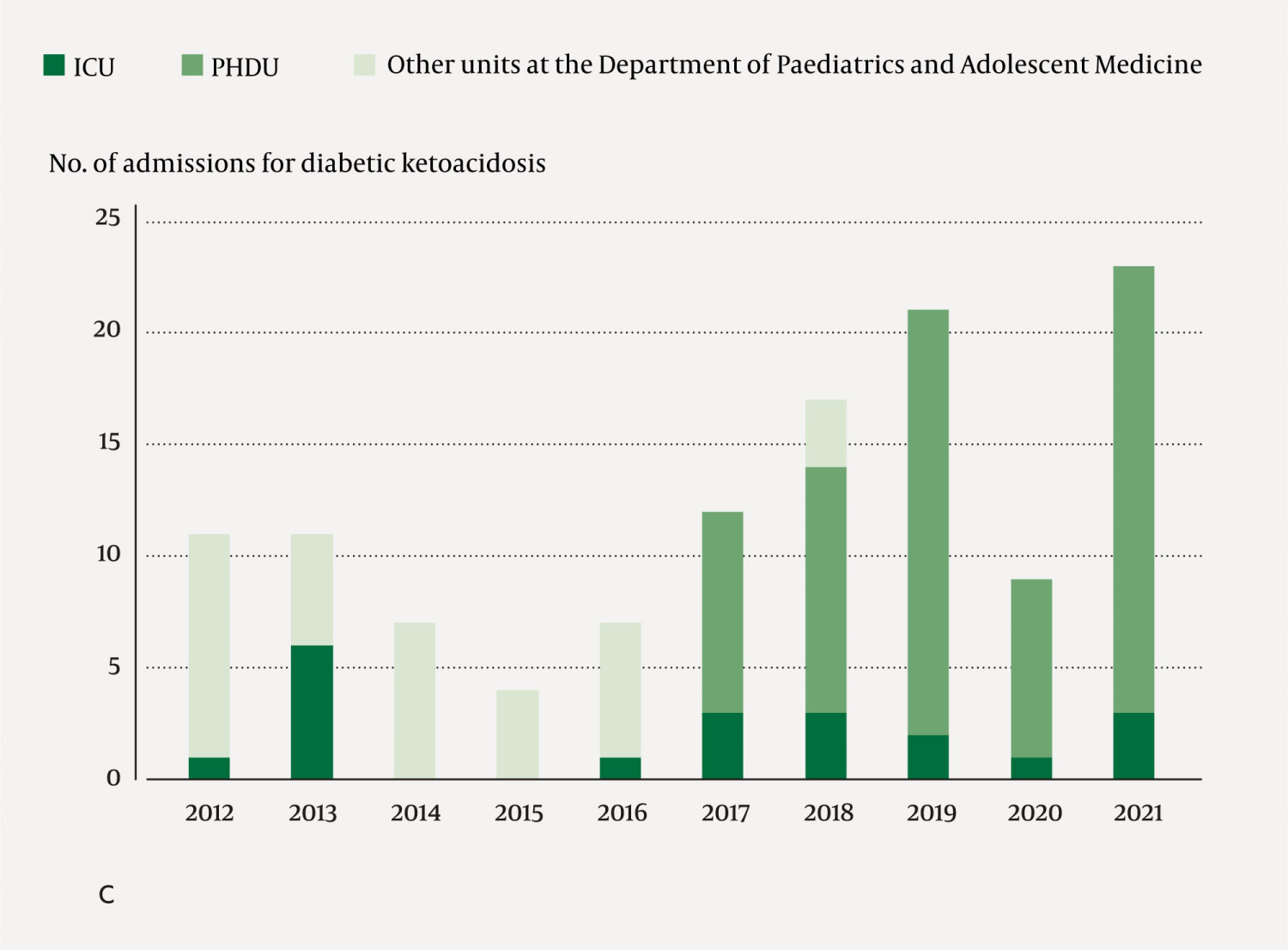

The proportion of patients admitted to the ICU with diabetic ketoacidosis fell from 20 % to 15 %, and patients admitted with sepsis decreased from 19 % to 12 %.

The proportion of ICU admissions directly from the PHDU increased from 10 % to 33 % between 2017 and 2021, and the proportion of ICU admissions that ended with a transfer to the PHDU increased from 10 % to 44 % in the same period.

High dependency or intermediate units in hospitals provide close monitoring and treatment for patients who are too ill to be cared for in a general ward, but do not require intensive care. This includes step-down care for patients who are discharged from intensive care units (ICUs) and step-up care in cases of acute deterioration in general wards (1, 2). This type of care for adult patients was introduced many years ago (3). The medical profession in Norway identified a need some time ago for similar high dependency care tailored for acutely and seriously ill children (4). This issue has become even more relevant as hospital patients are becoming more severely ill, require more resources and have a growing need for intensive care (5). Research on the use of paediatric high dependency units (PHDUs) is limited (1, 6), and knowledge on this in the Norwegian context is lacking.

In 2017, Haukeland University Hospital was one of the first hospitals in Norway to open a PHDU. This new unit has required training of staff, redistribution of personnel and additional resources. It is important that such priorities are evaluated. This article presents data from the quality register for the PHDU at the Department of Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine at Haukeland University Hospital, and seeks to examine whether the need for admission to an ICU changed after the unit was established.

Material and method

Since the opening of the PHDU at the Department of Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, all admissions have been recorded in the quality register for the unit. This study encompasses all patients aged 0–18 years who were included in the quality register in the period 13 February 2017 to 31 December 2021.

The Department of Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine at Haukeland University Hospital treats children and young people with medical problems, while patients with surgical diagnoses, burns and young people who are under the influence of a substance are generally admitted to other departments. In 2016, the age limit for which the Department of Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine is responsible increased from 0–15 years to 0–17 years. These age limits have not been absolute, and exceptions have been made for patients up to the age of 18 with chronic diseases who have not yet been transferred to an adult ward.

The criteria for transfer to the PHDU are admission to the Department of Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine and single organ failure or some other need for a higher level of care (4, 7). The PHDU is staffed by nurses who specialise in paediatrics or intensive care and a senior consultant trained in paediatric emergency medicine. The unit provides close monitoring of vital signs, fluid balance and clinical status, including the use of a peripheral arterial catheter, which is not available on a general ward. On the unit, it is possible to administer most infusions, handle chest drains and use non-invasive respiratory support in the form of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) and bilevel positive airway pressure (BiPAP). The criteria for admission to the ICU are life-threatening and potentially reversible single or multiple organ failure with a need for organ support therapy (7) that cannot be given in the PHDU. Examples of such conditions are respiratory failure requiring invasive mechanical ventilation, advanced treatment of status epilepticus, and circulatory failure with a continual need for hypotension therapy.

Upon discharge from the PHDU, an evaluation form is completed by a doctor and nurse. The information given on the form is supplemented with relevant information from the patient record and recorded in the quality register for the unit.

Data extracted from the quality register for this study included date and length of stay, sex, age, reason for high dependency care, diagnosis and treatment. In this study, the reason for transfer to the PHDU is grouped into seven categories, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1

Admissions to the PHDU 2017–21 and the ICU in the periods 2012–16 and 2017–21, by diagnostic group. PHDU = paediatric high dependency unit, CPAP = continuous positive airway pressure.

|

|

| PHDU |

| ICU | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

| 2017–21 |

| 2012–16 |

| 2017–21 | ||

|

|

| Admissions | Transferred to ICU1 |

| Admissions |

| Admissions | Transferred to PHDU1 |

| Diagnostic group |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

| Respiratory problem (total) | 337 | 16 |

| 72 |

| 69 | 24 | |

|

| Invasive mechanical ventilation | 0 | 0 |

| 32 |

| 48 | 18 |

| CPAP treatment | 257 | 15 |

| 21 |

| 16 | 6 | |

| Other | 80 | 1 |

| 19 |

| 5 | 0 | |

| Sepsis or suspected sepsis | 127 | 2 |

| 14 |

| 10 | 5 | |

| Seizures/neurological problems | 87 | 5 |

| 38 |

| 36 | 8 | |

| Complications of cancer2 | 74 | 8 |

| 35 |

| 37 | 14 | |

| Diabetic ketoacidosis | 68 | 1 |

| 8 |

| 12 | 3 | |

| Poisoning | 33 | 0 |

| 4 |

| 7 | 1 | |

| Other reasons | 125 | 4 |

| 14 |

| 16 | 4 | |

| Total | 851 | 36 |

| 185 |

| 187 | 59 | |

1The number of transferrals for the admissions in the column on the left.

2Encompasses all patients receiving cancer treatment.

Patients admitted to the Department of Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine who were also admitted to the ICU at Haukeland University Hospital during the five-year periods before and after the PHDU opened, in 2012–16 and 2017–21 respectively, were identified using the DIPS electronic patient record system (DIPS AS, Bodø, Norway). This includes children aged 0–18 with medical problems, while surgical problems and children registered via departments other than the Department of Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine were not included. The total number of admissions at the Department of Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine was obtained from the hospital's patient record system. The data were collected and analysed as part of the internal quality assurance process at the Department of Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine at Haukeland University Hospital. The study has been approved by the data protection officer in Western Norway Regional Health Authority (reference number 2018/11382). All registrations are documented in Microsoft Excel 2016, version 16.52 (Office, Los Angeles, CA, USA).

Results

In the period 13 February 2017–31 December 2021, 851 admissions were registered in the quality register for the PHDU, made up of 698 unique patients. This amounted to 851/16,708 (5.1 %) of the total number of admissions at the Department of Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine in the same period.

The median (interquartile range) age at admission was 1.5 years (7.6 weeks–7.4 years), and 385/851 (45 %) were below the age of one. The annual number of admissions at the PHDU has increased from 125 in 2017 to 247 in 2021. This accounted for 125/3,574 (3.5 %) and 247/3,271 (7.6 %) of the total number of patients admitted to the Department of Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine in these years.

The ICU had 185 paediatric medical admissions in the five-year period before the opening of the PHDU and 187 admissions in the five-year period after the opening. The ICU admissions accounted for 185/20,361 (0.9 %) and 187/16,708 (1.1 %) of all patients admitted to the Department of Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine in these five-year periods, respectively (Figure 1).

The median (interquartile range) stay in the PHDU was 23 (13–55) hours. In the ICU, the median (interquartile range) stay for paediatric medical patients was 27 (13–88) hours and 27 (15–79) hours in the five-year periods before and after the opening of the PHDU, respectively.

Among all the admissions to the PHDU, 414/851 (49 %) patients were transferred directly from the A&E department, while 360/851 (42 %) and 59/851 (7 %) of the admissions were transfers from general wards and the ICU, respectively. The remaining 18/851 (2 %) of the admissions were transfers from the postoperative ward or neonatal ICU.

Of the children admitted to the ICU after the opening of the PHDU, 87/187 (47 %) were admitted directly from the A&E department, 26/187 (14 %) after general anaesthesia, 36/187 (19 %) were transferred from the PHDU, while 38/187 (20 %) were transferred from general wards. The proportion of ICU admissions that were transfers from the PHDU increased from 4/41 (10 %) in 2017 to 13/39 (33 %) in 2021, while the proportion of ICU admissions that ended with a transfer to the PHDU increased from 4/41 (10 %) in 2017 to 17/39 (44 %) in 2021.

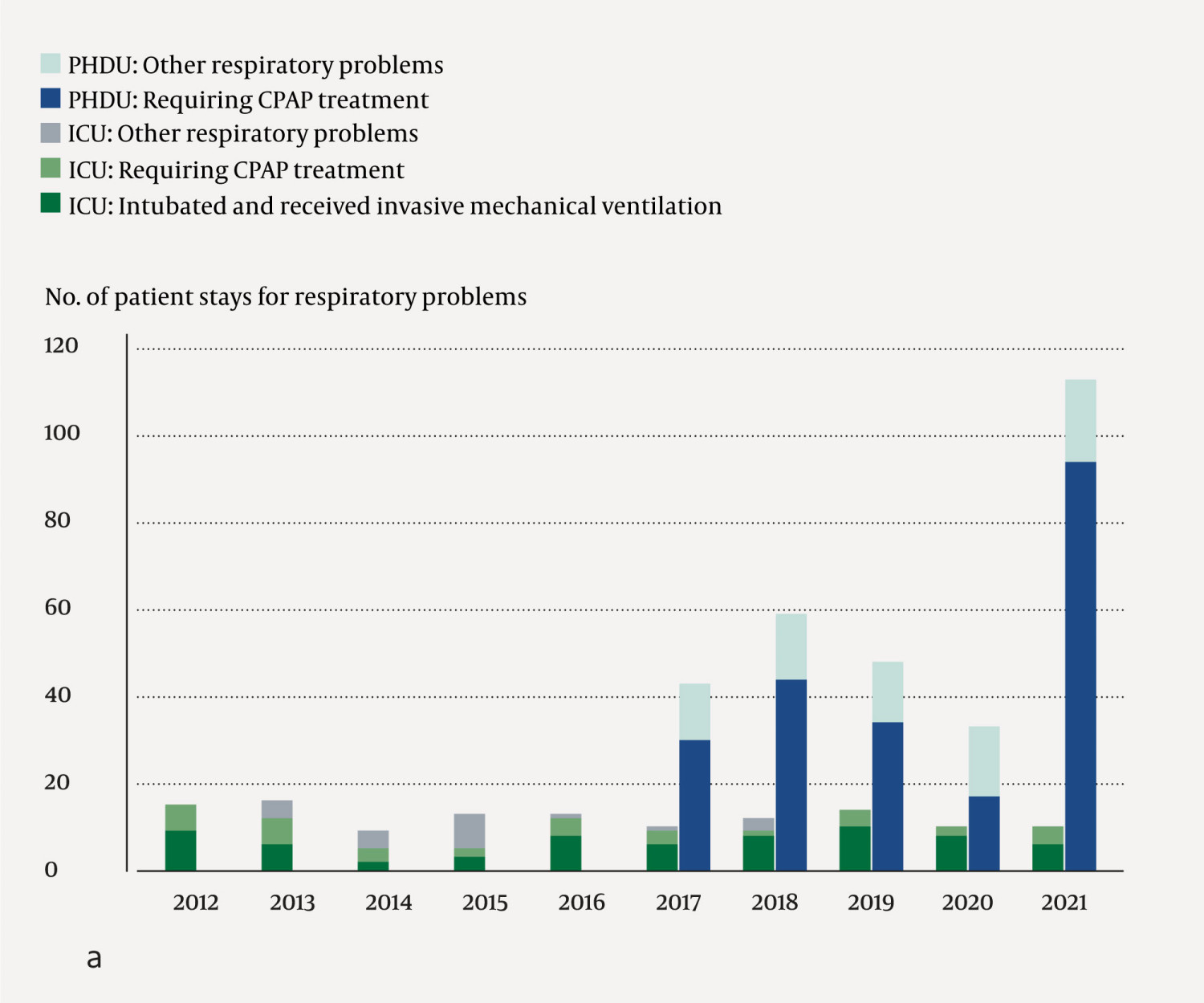

Respiratory problems were one of the main reasons for admission to both the PHDU and the ICU (Figure 2a). Children with respiratory problems accounted for 337/851 (40 %) of admissions to the PHDU. A need for CPAP treatment was the most common reason for admission, accounting for 254/851 (30 %) admissions (Table 1). The proportion of patients admitted to the ICU for respiratory problems was 72/185 (39 %) and 69/187 (37 %), respectively, in the five-year periods before and after the opening of the PHDU, and the proportion of these requiring invasive mechanical ventilation was 32/72 (44 %) and 48/69 (70 %), respectively, in the two five-year periods.

Sepsis or suspected sepsis was the reason for 127/851 (15 %) of the admissions at the PHDU. The corresponding proportion of patients admitted to the ICU was 14/185 (7.6 %) and 10/187 (5.3 %), respectively, in the five-year periods before and after the opening of the PHDU (Figure 2b). Viewed in relation to the number of patients with a confirmed diagnosis of sepsis at the Department of Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine as a whole, the proportion requiring intensive care fell from 14/72 (19 %) to 10/85 (12 %).

Diabetic ketoacidosis accounted for 68/851 (8.0 %) of the admissions in the PHDU and 8/185 (4.3 %) and 12/187 (6.4 %), respectively, of the admissions in the ICU in the five-year periods before and after the opening of the PHDU. The proportion of children admitted to the Department of Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine with ketoacidosis who were transferred to the ICU fell from 8/40 (20 %) in the five-year period before the opening of the PHDU to 12/80 (15 %) in the five-year period after its opening (Figure 2c).

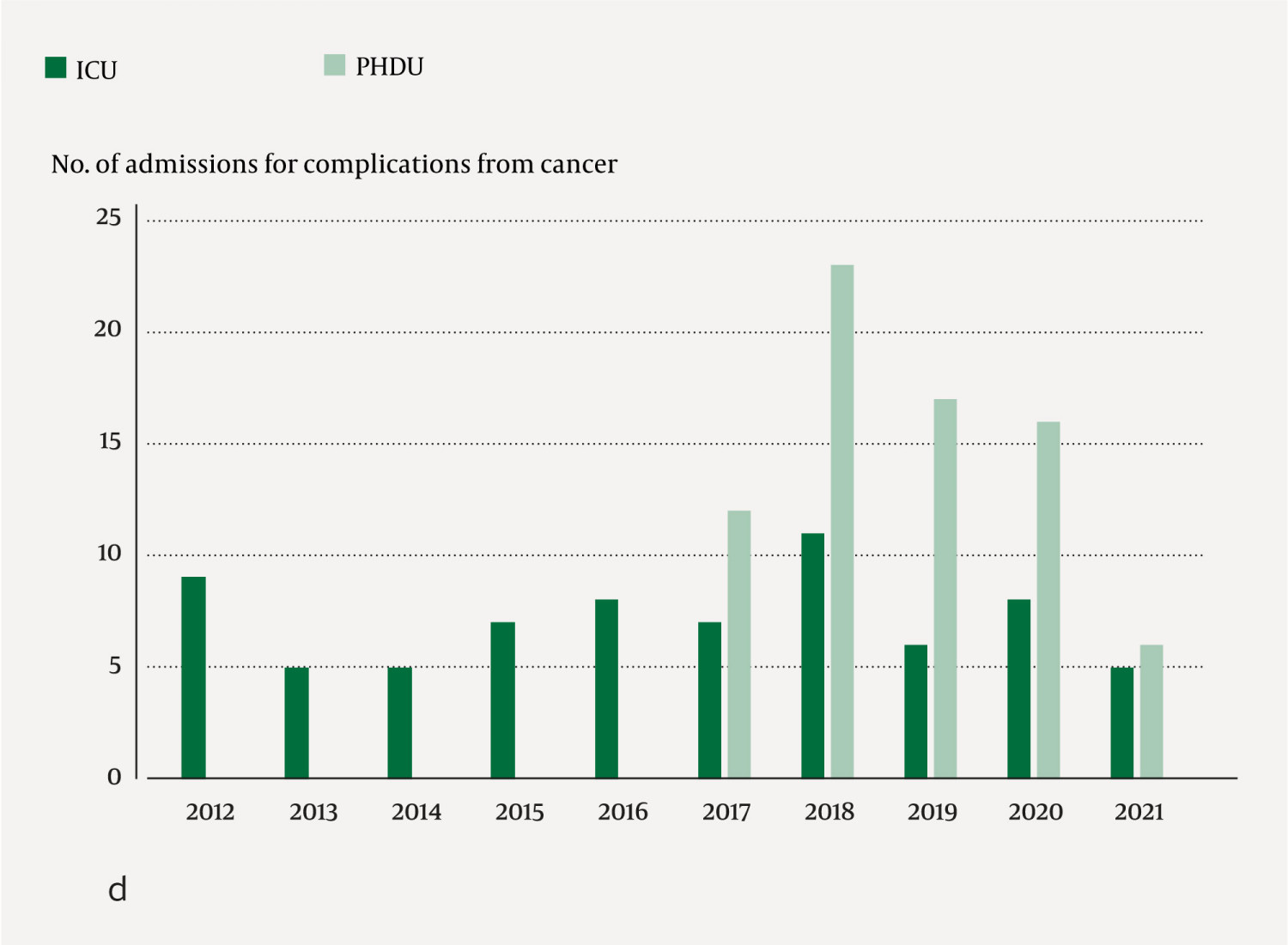

Children with complications from cancer accounted for 74/851 (8.7 %) of the admissions in the PHDU, but these patients had longer stays than other patients, with a median duration of 38 hours (interquartile range 20–90) compared to 23 (12–52) hours for the other patient groups combined. In the ICU, the group with complications from cancer accounted for 35/185 (19 %) and 37/187 (20 %) of the admissions, respectively, in the five-year periods before and after the opening of the PHDU (Figure 2d).

Discussion

We found that 5 % of children admitted to the Department of Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine were admitted to the PHDU. This was five times higher than the number requiring admission to the ICU. The number of transfers from the Department of Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine to the ICU was stable from the five-year period before to the five-year period after the opening of the PHDU, but the composition of patients in the ICU changed in a way that may indicate more appropriate use of ICU beds. A lower proportion of patients with diabetic ketoacidosis and sepsis were transferred to the ICU, while a higher proportion of the children who were transferred to the ICU for respiratory problems required invasive mechanical ventilation.

The number of admissions at the PHDU increased every year until 2019. It then fell slightly in 2020 but increased sharply in 2021, largely in connection with a widespread epidemic of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) that year. Many of the paediatric RSV patients were admitted to the PHDU for CPAP treatment. The decrease in 2020 was probably due to the COVID-19 pandemic, when fewer children were hospitalised due to the reduced incidence of other viral infections as a result of infection control measures (8).

It is estimated that 10 % of patients admitted to paediatric and adolescent medicine departments will need to be admitted to a PHDU (4). We observed a gradual increase in use of the PHDU in the years immediately following the opening of the unit at Haukeland University Hospital. This trend has also been seen at hospitals in England (6). However, use is still slightly below what was expected. The Norwegian standard for paediatric high dependency care recommends that children who need oxygen supplementation in the form of high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) therapy should be admitted to a PHDU (4). At the Department of Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine at Haukeland University Hospital, however, such treatment is carried out on general wards, which may partly explain the discrepancy between the estimated and actual need for paediatric high dependency care. We found that the median stay at the PHDU was just less than one day, i.e. slightly less than the expectation in the Norwegian standard for paediatric high dependency care of 1–2 days (4) as well as figures from England, where the average stay was 1.8 days (9).

In the ICU, no major differences were recorded in the number of paediatric medical admissions over the past ten years. This is in contrast to figures from England for the period 2001–10, which show a gradual decrease in the number of ICU admissions after the opening of PHDUs (9). This trend has also been observed following the opening of high dependency units for adults (3). For most of the diagnostic groups, the number of admissions was almost the same or slightly lower in the five-year period after the opening of the PHDU, except for the diagnostic group diabetic ketoacidosis. However, the incidence of diabetic ketoacidosis increased sharply during the period of the study, and although the number admitted to the ICU rose from eight to twelve in the five-year periods before and after the opening of the PHDU, this represented a reduction in the percentage with diabetic ketoacidosis who were admitted to the ICU from the Department of Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. This is in line with the national expectation that diabetic ketoacidosis can be treated in a PHDU(4).

The only diagnostic group with a marked increase in the number of ICU admissions was among children given invasive respiratory support, which is not available in the PHDU and thus indicates an appropriate use of ICU beds. Several of these patients required invasive mechanical ventilation following operations or procedures under anaesthesia, often as part of a complicated course of illness. The increase in this group is consistent with reports indicating that the hospital population is becoming more severely ill, requiring more resources, and that the need for ICU beds is growing (5). In almost half of paediatric ICU patients, the ICU stay was at the beginning of the hospital stay, and many patients need initial stabilisation in the ICU, regardless of how well the PHDU functions.

Many patients in both the PHDU and the ICU are admitted due to respiratory problems. Non-invasive ventilation support can be provided in the PHDU and can thus help to relieve the workload of the ICU. The number of children who only received CPAP treatment in the ICU and did not require invasive mechanical ventilation decreased in the five-year period after the PHDU was opened. The number of children who need CPAP varies considerably from year to year, and this is often closely linked to winter epidemics of viral respiratory infections. The observation period in our study is relatively short, and it is too early to conclude whether the introduction of a PHDU has reduced the workload of the ICU in relation to children requiring CPAP treatment.

Suspected sepsis is the second most common diagnostic group in the PHDU, as was also the case in the adult population at the high dependency unit at Akershus University Hospital in 2014 (10). We identified a downward trend in the number of sepsis admissions in the ICU after the opening of the PHDU. This may be due to the fact that resources are available to care for these patients in a PHDU, which has more staff, better routines and more advanced equipment than a general ward (4). The increase in the total number of admissions for sepsis in the PHDU is also greater than the decrease in the ICU. This is probably due to increased awareness both in Norway and internationally that children with suspected sepsis should be given high dependency care in order to clarify their diagnosis quicker and consequently provide better treatment (11).

Children with cancer have a higher risk of other serious diseases than their peers (12). We therefore grouped all children receiving cancer treatment into one diagnostic category. This explains why the number of admissions in this group is higher than in other reports (9, 13). The opening of the PHDU did not reduce the number of children with cancer in the ICU.

The PHDU functions as a step-down unit or a step-up unit depending on the child's need for high dependency care (1, 2). In the years following the opening of the PHDU, the number of transfers between this unit and the ICU increased. This may indicate that the interaction between the departments has improved and that the PHDU functions as an intermediate care unit. Optimised interaction enables the PHDU to help identify patients with a real need for intensive care and shortens the time they spend in the ICU.

One of the strengths of this study is the prospectively collected data, which includes all admissions since the opening of the PHDU at the Department of Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, Haukeland University Hospital, which is a hospital that receives a wide range of patients from a large geographical area.

One of the weaknesses of the study is that the unit is relatively new, and it is therefore too soon to make comparisons that require a longer observation period, as has been done in various ten-year reports (9). Furthermore, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, 2020 and 2021 are probably not completely representative years (8). In addition, the study is based on documentation from healthcare personnel treating patients, and errors in recorded information can therefore give a skewed picture.

Conclusion

The opening of the PHDU has not reduced the total number of paediatric medical admissions to the ICU, but may have reduced the workload of the ICU in relation to children with diabetic ketoacidosis, respiratory problems and suspected sepsis.

The article has been peer-reviewed.

- 1.

Ettinger NA, Hill VL, Russ CM et al. Guidance for Structuring a Pediatric Intermediate Care Unit. Pediatrics 2022; 149: e2022057009. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 2.

Plate JDJ, Leenen LPH, Houwert M et al. Utilisation of Intermediate Care Units: A Systematic Review. Crit Care Res Pract 2017; 2017: 8038460. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 3.

Fox AJ, Owen-Smith O, Spiers P. The immediate impact of opening an adult high dependency unit on intensive care unit occupancy. Anaesthesia 1999; 54: 280–3. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 4.

Norsk barnelegeforening. Standard for barneovervåkningen i Norge. https://www.helsebiblioteket.no/innhold/retningslinjer/pediatri/generell-veileder-i-pediatri/18.standard-for-barneovervakning-i-norge Accessed 28.10.2022.

- 5.

Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health. High dependency care for children - time to move on. https://www.rcpch.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2018-07/high_dependency_care_for_children_-_time_to_move_on.pdf Accessed 28.10.2022.

- 6.

Morris KP, Oppong R, Holdback N et al. Defining criteria and resource use for high dependency care in children: an observational economic study. Arch Dis Child 2014; 99: 652–8. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 7.

Norsk anestesiologisk forening og Norsk sykepleieforbunds landsgruppe av intensivsykepleiere. Retningslinjer for intensivvirksomhet i Norge. https://www.legeforeningen.no/contentassets/7f641fe83f6f467f90686919e3b2ef37/retningslinjer_for_intensivvirksomhet_151014.pdf Accessed 28.10.2022.

- 8.

Kruizinga MD, Peeters D, van Veen M et al. The impact of lockdown on pediatric ED visits and hospital admissions during the COVID19 pandemic: a multicenter analysis and review of the literature. Eur J Pediatr 2021; 180: 2271–9. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 9.

Linnitt J, Davis P, Walker J. A summary report of data from the South West Audit of Critically Ill Children from 2001-2010. https://www.picanet.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/25/2020/02/SWACIC-Report-2001-2010-Final-Version-20-02-12.pdf Accessed 28.10.2022.

- 10.

Morland M, Haagensen R, Dahl FA et al. Epidemiologi og prognoser i en medisinsk overvåkningsavdeling. Tidsskr Nor Legeforen 2018; 138: 734–9.

- 11.

Cruz AT, Lane RD, Balamuth F et al. Updates on pediatric sepsis. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open 2020; 1: 981–93. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 12.

Simon A, Ammann RA, Bode U et al. Healthcare-associated infections in pediatric cancer patients: results of a prospective surveillance study from university hospitals in Germany and Switzerland. BMC Infect Dis 2008; 8: 70. [PubMed][CrossRef]

- 13.

Rushforth K, Darowski M, McKinney PA. Quantifying high dependency care: a prospective cohort study in Yorkshire (UK). Eur J Pediatr 2012; 171: 77–85. [PubMed][CrossRef]